As revenues boom, Queen’s Park tightens the screws

This article is republished with thanks to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA). It originally appeared in its publication The Monitor.

In 2020, front-page stories on the Ontario budget were all about spending—huge, huge spending to combat COVID-19. Now, as 2021 wraps up, rising provincial revenues are getting their time in the spotlight.

Back in March, Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy tabled a 2021-22 budget that projected only a slight improvement in revenue over last year. By the time of his Nov. 4 fiscal update, though, the minister was seeing a revenue increase that was nearly 10% higher than his earlier prediction. Money was pouring into provincial coffers. Suddenly, the minister had $14.6 billion he hadn’t banked on.

As it turns out, massive federal spending to shore up the economy was not only good for people and businesses; it was also very good for provincial tax revenues.

With $14.6 billion in found money, the minister allocated $11.6 billion to reducing the deficit and $4 billion to fighting COVID-19 in this fiscal year. The budget for base program spending for 2020-21—money normally spent on programs when there isn’t a global pandemic—has been pared down by $800 million compared to the plan in March.

The largest share of that reduction, a $500 million cut to planned spending on education, is significant, and the government plans to keep squeezing school funding over the next two years. But other sectors will be hit even harder.

In dollar terms, the biggest bite will come out of health care.

In its November update, the government vowed to increase program spending by an average of 3% per year over the next two fiscal years. Unfortunately, that’s not enough: because of inflation, population growth, and the health challenges of an aging population, spending must grow by more than that just to maintain services at current levels. In June, the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) estimated that spending must increase by at least 3.3% overall to maintain services. Cost pressures are highest in health, where spending must grow by 4.4% to maintain services, the FAO says.

In the current context, these numbers are almost certainly too low: inflation has gone up noticeably since the spring, and everything hospitals, schools, and the rest of the public sector needs to buy will be affected. Using the FAO’s cautious estimates, though, we can see where spending falls short and where it is enough to maintain current levels.

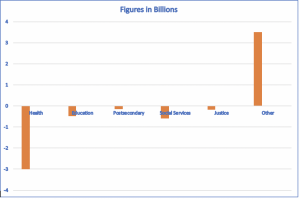

As the graph shows, the province plans to spend less than needed in five out of six areas between 2021-22 and 2023-24. At the end of the two years, the health care sector will be short $3 billion; education will be short $480 million; social services will be short $600 million; justice will be short $190 million; and post-secondary education will be short $150 million.

Funding shortfall or increase relative to current need, by

budget sector, 2021-22 to 2023-24, in $billions

Sources: 2021 Ontario Budget; 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review; Financial Accountability Office, Economic and Budget Outlook, Spring 2021, and author’s calculations.

For an interactive chart click here

The only category that will receive more money than it needs to maintain current service levels is the “Other” category.1 “Other” includes many ministries, from Agriculture to Treasury Board, but of these, only those ministries dealing with infrastructure, transportation, and northern development merited mention—and money—in the minister’s fall update.2 Ministries in the “Other” category will apparently receive $3.5 billion more, over two years, than they would need to maintain current services.

Or will they? The government has plans to spend some of this “Other” money, but not all of it. The fall statement says “The Other Programs Sector includes fiscal flexibility that may be reallocated across government programs to navigate risks that may arise over the medium term.”

This is highly unusual. The normal way to budget for the unexpected is with reserve funds. By creating a slush fund within the “Other” category, the government can now spend new money (in an election year) without affecting its overall bottom line.

But public services need money now.

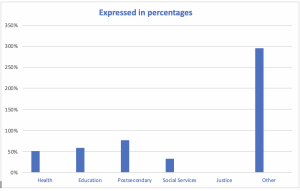

Expressed in percentage terms, the justice sector will see exactly none of the money it needs to keep up with cost pressures; the social services sector will receive 33% of the increase it needs; health care will receive 52%; education, 59%; and post-secondary education, 77%. Meanwhile, the “Other” sector will see 295% of what it would have needed to maintain the services “Other” ministries normally provide.

Interesting.

Percentage of needed spending increase budgeted for, 2021-2022 to 2023-24

Sources: 2021 Ontario Budget; 2021 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review; Financial Accountability Office, Economic and Budget Outlook, Spring 2021, and author’s calculations.

For an interactive chart click here

Throughout 2021, Queen’s Park has stated that its fiscal recovery from COVID-19 “will be built on a strong foundation for growth, not painful tax hikes or cuts,” but this is misleading. The small increases in overall nominal spending that are planned at the provincial level translate to real cuts to public services at the level of individuals and families.

In June, the FAO stated that the government’s long-term plan, as detailed in the March budget, “relies on prolonged spending restraint requiring significant and permanent cost savings that would lower real program spending by $1,281 per Ontarian.”

Nothing in the fall update suggests Ontario is on a different trajectory now.

—

1 “Other” program ministries include Transportation; Energy, Northern Development and Mines; Finance; Treasury Board Secretariat; Municipal Affairs and Housing; Government and Consumer Services; Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries; Labour, Training and Skills Development; Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Infrastructure; Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade; Environment, Conservation and Parks; Natural Resources and Forestry; Board of Internal Economy; Seniors and Accessibility; Indigenous Affairs; Executive Offices; and Francophone Affairs as well as Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. Source: FAO.

2 The minister also sketched out plans to make specific improvements in health care, but since there is no plan to increase real per capita spending in health care over the two years, the cost of these improvements will necessarily be paid for out of current health care budgets, i.e., through spending reductions in other areas of health care.

Randy Robinson is the Ontario Director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter at @RandyFRobinson