Beginning the journey of reconciliation: Orange Shirt Day in elementary schools

With the collaboration and support of the Orange Shirt Society, Alberta Educator Robin Drinkwater developed a curriculum for young people from Kindergarten to grade 6 based on Orange Shirt Day. This is the day set aside to acknowledge the destruction wrought by the “Indian Residential Schools” that developed soon after Confederation as “part of a coherent policy to eliminate Aboriginal people as distinct peoples and to assimilate them into the Canadian mainstream against their will.”1 An estimated 150 000 First Nation, Metis and Inuit children passed through these alien, harsh and brutal places, the last of which closed in the late 1990s.

I will never forget sitting in a staff meeting at the end of the day, in early September 2016. As the meeting ramped into full swing, my principal announced we would be observing Orange Shirt Day on September 30th. At the time, I had no idea what Orange Shirt Day was, let alone how to go about teaching it.

I learned quickly that it was started by Phyllis Webstad to honour Residential School survivors and acknowledge the dreadful impacts these schools had on the Indigenous children who attended them. I discovered that Phyllis wore an orange shirt her grandmother had purchased for her first day of school; that it was taken away by the people who ran it. So now I knew what it was about and why the colour orange was significant; that was helpful. As conversation continued, the reality sank in that Orange Shirt Day meant taking up the topic of Residential Schools in our Kindergarten to Grade 6 classrooms This task felt daunting as many, myself included, had never learned much about Residential Schools in our own education and were not even sure where to begin. This was not simply an ask by an administrator, it was our job and was going to be part of our Alberta Teaching Quality Standards. How on earth was I going to meet our legal obligations as educators while simultaneously trying to do justice to such a meaningful and significant topic?

When educators are faced with challenges, we model for our students what we would like to see them do. I learned, I made mistakes, I learned more, I asked a lot of questions, I found authentic resources, and I was honest about how little I knew. Fast forward and here I am a whole lot of learning later, as a non-Indigenous educator sharing Orange Shirt Day: A Kindergarten to Grade 6 Curriculum. If you explore the topic in an age-appropriate way, it is my belief and sincere hope that our youngest learners can begin the journey of education for reconciliation as soon as they enter our school system. Children will not understand the full impact or devastation caused by Residential Schooling while in elementary school, however, we can establish a foundation on which to continue to grow their understanding throughout their Kindergarten to Grade 12 education.

Curriculum Overview

One of the things I learned quickly was that, as Starleigh Grass states in her TedEx West Vancouver talk, in order to understand what was lost through Residential Schooling we must first understand the rich cultures and knowledge that Indigenous peoples hold. Without an understanding of Indigenous cultures and knowledge systems, without valuing what those cultures and knowledge systems have to offer, how can we study the loss with any meaning?

of Orange Shirt Society

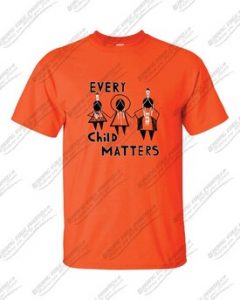

This is where I chose to start. The Kindergarten through Grade 2 curriculum is designed to teach students about Indigenous cultures along with focusing on the slogan for Orange Shirt Day: “Every Child Matters”. Students explore how children matter in their families, classrooms, schools, and greater communities while also being exposed to elements of Indigenous cultures that demonstrate how Indigenous children, their roles, and their contributions are valued in their communities.

The introduction of the idea of Residential Schooling takes place in Grade 3 once students have the foundation of understanding that Indigenous peoples have rich and meaningful cultures, traditions, languages, and ways of knowing. Once students have explored their own connection to the communities they live in, they can more deeply understand the devastating effects of Indigenous children removed from their homes would have on their communities. Hopefully, they can begin to appreciate the anguish Indigenous children faced when they entered a residential school.

Students in Grade 3 do not delve into the atrocities of residential schooling. They look at age-appropriate loss: not being with their family, not wearing the clothes they are used to, not being able to speak in their language, or not having their toys with them. Students are able to empathize with these ideas and begin to understand that residential schooling would have been hard, scary, and very different then what schooling is like for them. This introduction allows for students to continue their learning and, each year, delve more deeply into the ways residential schooling attempted to destroy Indigenous culture and community, and to appreciate the resiliency of Indigenous peoples.

In Grades 4 and 5, students take a closer look at an individual story of someone attending residential school, and subsequently, the return to life back home. We use the books Fatty Legs and A Stranger at Home: A True Story by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton. This allows students to connect, through literature, with the experience of being in a residential school, where the cultural practices are completely foreign, while facing the trauma of being removed from one’s home and family. Students can see that, for young Indigenous people returning home, it was not an easy transition. Residential school survivors often felt isolated and as though they belonged nowhere. They did not fit into the settler world at residential school, and they no longer fit into their own communities. Students examine the struggles of Olemaun in both these situations and are able to have a greater understanding of the difficulties residential school survivors faced while attending and after leaving the residential school system.

With this depth of background in residential schooling, Grade 6 students look at differing views on residential schooling throughout history. They check different media presentations of residential schooling and see how society’s views on this have changed over time. Students are asked to think critically about Canadian history and acknowledge that there are parts of it that we must not repeat, thus solidifying the need to repair relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in our country. This is foundational understanding that can extend beyond the curriculum because it helps students develop into global citizens understanding the impacts of history beyond our borders. The U.S. has its own history of Native American boarding schools. It’s the same for Australia, where a “stolen generation” of an estimated 10 500 Aboriginal people were taken from their families to mission schools so they could be trained to become domestic servants. Even today, the separation of Uigher children from their families in China and forcing attendance at “re-education camps” will have long term, horrific impacts on an entire group of people; people who have value to offer in our world.

Honouring Dual Pedagogy

The focus of the Kindergarten to Grade 6 lessons are two-fold: to learn about Indigenous cultures and the impact on Indigenous peoples caused by the Residential School system, and just as important, to use and recognize the value of Indigenous ways of knowing within the elementary classroom. Since I have presented a summary of the content of this curriculum, I now turn to the latter: how Indigenous values and ways of knowing should permeate teaching practice beyond these lessons. This shows students that both Euro-western ways of knowing and Indigenous ways of knowing can co-exist and be valued equally in the same space, at the same time and benefit every child’s learning experience.

The lessons throughout the Orange Shirt Day: A Kindergarten to Grade 6 Curriculum, focus on students not simply reading, writing, and representing. The importance of listening and speaking play a key role. Talking circles, based on Indigenous sharing circles, are used across all grades to help students communicate their understanding and listen to the views of others. In grades 4, 5, and 6 the use of the talking circle continues, and the concept of witnessing is added. This allows students to learn that there were different ways that oral traditions are manifested and that there is equal value in taking the role of speaker and of listener, or witness.

Respect for Indigenous people who own these traditions and learning is a key issue. When referring to traditions held by Indigenous communities it is important to acknowledge where those practices come from and how they are traditionally used. It is critical to ensure that you are explicit and clear with students that the classroom activities based on those practices, are not the same as traditional practices. As educators, we may not even hold the rights and permission to use those practices; in many cases, we are not following all protocols and traditional uses of these ways of knowing, being, and doing. Rather, we are recognizing the benefit of those traditions and altering them to best benefit all student learning.

This is also important because there are many traditions that require proper teachings and permissions to lead them. In my classroom, we use a talking circle and I always ensure that we understand the traditional practice, but I acknowledge that I do not have the right to make or use a talking stick. We select another meaningful object for our classroom community and use that. This demonstrates for students that there is value in a practice, and we can learn from it without making any claim that it is ours. We want to ensure, that in trying to communicate the importance of these ways of knowing, being, and doing, we are not appropriating Indigenous cultures.

As teachers embark on this work within their classrooms it is critical that they take the time to examine their teaching practices and reflect openly and honestly on what is valued in their classes. Teachers need to explore and enhance their awareness of personal biases, so they can begin to tackle the task of decolonizing classrooms. By examining what is valued and creating the space to value other ways of knowing, being, and doing within the classroom, teachers are taking the first steps towards decolonization- they are including all students, regardless of cultural background, learning style, or personal preference, in the learning process an. For example, look at the talking circle and the value placed on oral language and listening openly to one another’s ideas. This alone, acknowledges that there are ways other than Euro-Western ways to be knowledgeable. It helps to create an environment where students can explore Indigenous culture and understand it, though it may be different from the ways of knowing, being, and doing they are familiar with. There is richness and value in the systems and processes used throughout Indigenous culture.

At this time, the classroom can welcome authentic Indigenous voices into the learning of all students. For example, to best understand why, in Fatty Legs, Olemaun struggles with learning to read and write in English, students have already discovered, through decolonizing pedagogy, how valuable oral traditions are, so they can clearly see both the value and differences in these academic skills. By Indigenizing the learning space, students and teachers alike can explore learning in new ways and broaden their understanding of what it means to be knowledgeable in a particular area or way.

When making use of Indigenous content throughout the Orange Shirt Day lessons, it was important to ensure that the literature and resources used to share knowledge about the Residential School system were authentic- told through the voices of people who experienced this atrocity. All literature used to address Residential Schooling is by Indigenous authors, allowing for an authentic experience to be presented to students as they learn about a topic that is difficult to fathom for many members of Canadian society today. Finding literature and resources that are authored by, or created in collaboration with Indigenous people, gives credibility to the material being presented to students.

In the development of these lessons, I learned a great deal and shared my work with Indigenous educators and people to ensure that the use of Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing were appropriate. I know that I am not an expert. I know that I can never understand the lived experience of a group of people who have experienced a different history than me, live a different culture, and daily experience than I do. What I can do is learn, ask questions, and share my learning with others.

Former Senator, Murry Sinclair, said, “It was the educational system that has contributed to this problem in this country and it is the educational system, we believe, that is going to help us get away from this.” By exploring Orange Shirt Day in elementary schools, we are allowing young people to begin this journey of learning early, something that should give them a deeper understanding of the history of Canada and the treatment of Indigenous peoples, both past and present. That deepened understanding and knowledge of the Residential School system can help to develop citizens who are able to make meaningful progress on the journey towards reconciliation in Canada.

Books and other materials about the Orange Shirt Society – including the lessons described above- are available at Medicine Wheel Education

Robin Drinkwater is a full time classroom teacher in Calgary

1. Truth and Reconciliation Final Report p.10