Behind “First Voices,” TDSB’s mandatory course on Indigenous studies- an interview with student trustee Isaiah Shafqat

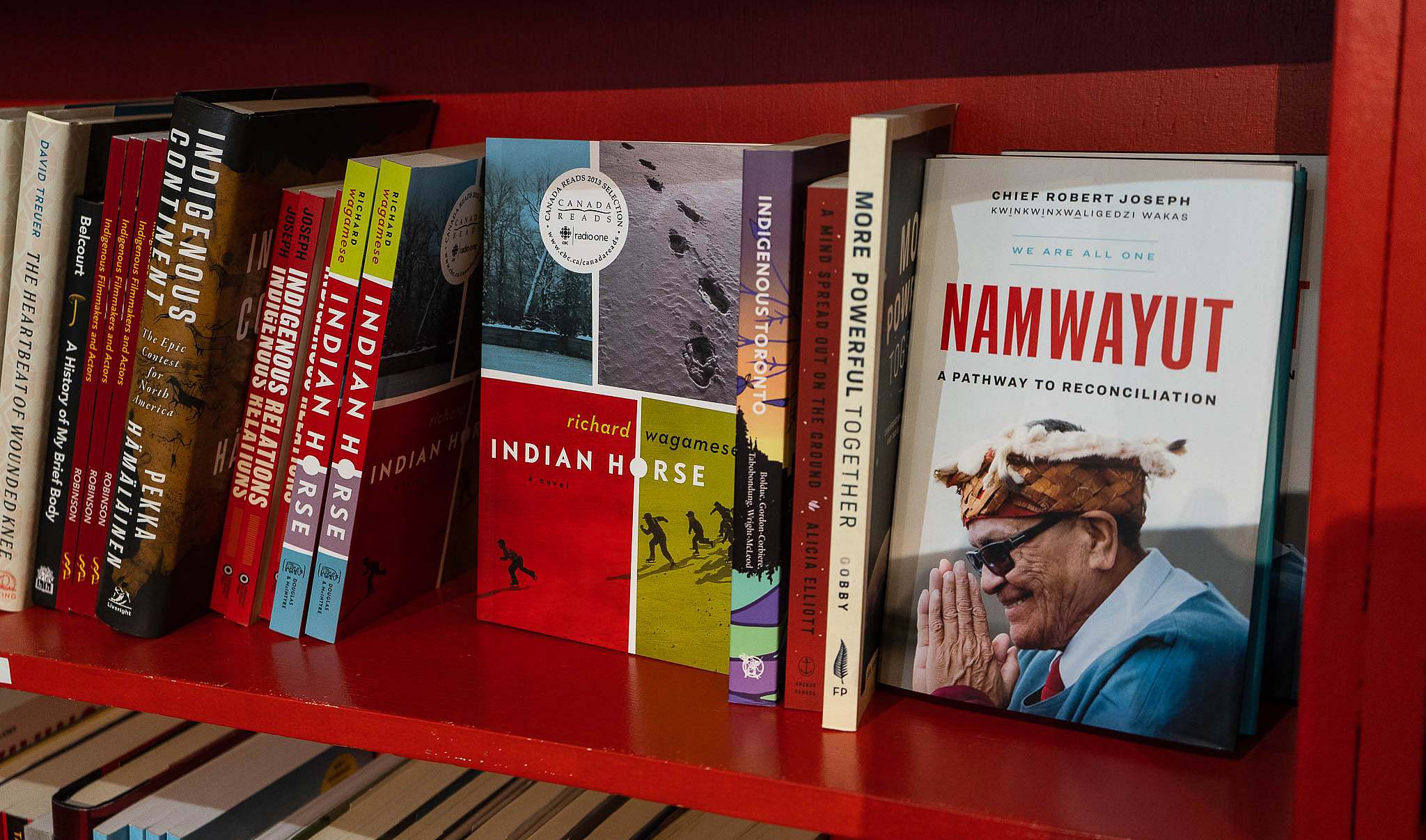

On February 1, the Toronto District School Board approved a motion to require secondary students to take the Grade 11 English Course: Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Metis and Inuit Voices . Called First Voices, it uses texts from Indigenous writers, so students can learn more about their cultures, histories and social/political conditions. All of this supports typical goals of English courses concerning critical reading, informed discussion, research and writing. But it goes beyond typical English courses in that it introduces students to “culturally appropriate listening practices” set in an historical context of social, economic and political forces that so fundamentally affected Indigenous histories.

TDSB staff have been told to prepare a report by June explaining when and how the course will be rolled out in the board’s 110 secondary schools.

The person behind the move was Indigenous student trustee, Isaiah Shafqat who is of Mi’kmaq background. He graciously consented to the interview which appears below.

School: By making this course compulsory, the TDSB has to put its money where its mouth is as far as its support for equity is concerned. Would you explain how how you came to your position that the First Voices course needed to be mandatory.

Isaiah Shafqat: I ran for student trustee almost three years ago now. I was appointed by the Elders Council of the TDSB and had been reappointed for a year – it’s a yearly position. In grade 11, I took the NBE3 course which is “The Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Metis and Inuit Voices” and, having taken the course and reading the books that were in it and listening to the stories that were told, I was able to see that it needed to be mandatory. Every single student who graduates from the TDSB needs to understand these basic principles – these basic injustices that take place. We can’t continue to live in a world where Indigenous issues are not at the forefront or aren’t spoken about. You know, it was clear that people didn’t know about the atrocities that took place during residential schools when we saw the shock in society with the recovery of the unmarked graves.

Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Metis and Inuit Voices” and, having taken the course and reading the books that were in it and listening to the stories that were told, I was able to see that it needed to be mandatory. Every single student who graduates from the TDSB needs to understand these basic principles – these basic injustices that take place. We can’t continue to live in a world where Indigenous issues are not at the forefront or aren’t spoken about. You know, it was clear that people didn’t know about the atrocities that took place during residential schools when we saw the shock in society with the recovery of the unmarked graves.

So, knowing that this course taught me so much about Indigenous world views, histories, perspectives – and that there was the need for the same level and quality of education, I was like: “This needs to be mandatory.” I took it to students; I took it to staff at the TDSB, our Elders Council and after lengthy discussion of almost two years, I submitted a motion with the support of two adult trustees and it passed.

Who were the trustees?

IS: Trustee Shelly Laskin and Trustee Michelle Aarts and they did it on behalf of myself, Student Trustee Naomi Musa and Jeffery Osaro

You said you consulted with School Board Elders, could you give us little more detail about that?

IS: Sure, the TDSB has an elders council – about 4 elders who guide the work we do within Indigenous education. So I took it to them and asked them what did they think: would this be a good idea, was this important – and their answer was “yes.” They’d talked about this for years and they were excited for this to happen – to see some actual movement on the implementation of it and so they were enthusiastic about the motion and very happy that it passed.

Can you see this idea happening with other groups of students: Black students, Muslim students, for instance. Might there be some sort of course developed for students to better understand their backgrounds?

IS: There could be; the Ministry currently doesn’t offer any course of that nature. But it’s also important to remember that Indigenous people are distinct and we do not fall under the same categories of white, Black and other people of colour. We are the first people of this land and our stories and perspectives are so different compared to the colonial or western narrative. And so, there’s a different relationship between Indigenous education and making that compulsory and say making “Deconstructing Anti-Black Racism” mandatory.

How well do you think students will accept this course? Might it be used by other boards?

IS: What I’ve heard from students right now: they’re happy and excited. All the students I’ve known to take the class, have enjoyed it and had positive experiences. I think it will cause a ripple effect- that TDSB is the largest school board in Canada and the fourth largest in North America. When we put our money where our mouth is – action through the words – that sends a message. We’re not the first board to do this, but we’re the largest and that sends a really strong message about the importance of Indigenous education.

Toronto Star columnist, Heather Mallick said in a recent column that it’s great that you want a mandatory course with Indigenous writers but argues: “I want students to be smarter. Shafqat wants them to be nicer. I’m not sure how either of us can achieve these aims.” She goes on to say that we need the work of these centuries-old writers to teach kids about thinking, about the broader elements of literature. What do you say to that?

IS: I disagree. Even to say that I want students to be nicer, that goes without saying. We need to build tolerance and respect within society, but this course teaches the same core principles of writing – how to write essays, grammar and so forth. So, we’re really not changing anything about the course itself; we’re just changing the literature that’s studied. To say that we need what are known as the “classics” like Shakespeare – written by white men – to teach us how to think, I think is a very Euro-centric view of what thinking is or how knowledge is assessed. Knowledge and thinking come in so many forms – to only rely on a book or an author from hundreds of years ago – it doesn’t move us forward.

respect within society, but this course teaches the same core principles of writing – how to write essays, grammar and so forth. So, we’re really not changing anything about the course itself; we’re just changing the literature that’s studied. To say that we need what are known as the “classics” like Shakespeare – written by white men – to teach us how to think, I think is a very Euro-centric view of what thinking is or how knowledge is assessed. Knowledge and thinking come in so many forms – to only rely on a book or an author from hundreds of years ago – it doesn’t move us forward.

So you can do the same job of teaching about thinking with any good writer – any good Indigenous writer.

IS: I would even argue that you can go further, because it’s issues that are contemporary and issues that are unresolved and so I think it will spark critical thinking for students about how they can be part of change, how they can be part of the solution.

A couple of trustees voted against your motion one of them saying “implementation is not supported” through pedagogical analysis. What do you say to that?

IS: I think their comments were based on a misunderstanding. There’s the notion that we’re getting rid of Shakespeare as a whole and replacing an English course with a non-English course. That’s not true. The trustee who was asking questions about pedagogical analysis – that will all be provided in the upcoming staff report to the Board. The questions or comments that were made were not directly connected to the motion. The motion was for the report to be presented and with the motion, MBE3 becomes mandatory. The implementation of this course will be successful and will be done well and that’s why it’s gradual. We can’t make all 110 secondary schools offer this course properly overnight. The comments I think, are based on a misunderstanding of the motion and I think just a general lack of knowledge with Indigenous authors and literature.

What are your hopes for this- as an Indigenous student- going beyond the TDSB?

IS: As an Indigenous student, I hope this becomes mandatory in all boards. To have Ontario centre Indigenous authors in a compulsory course would be a really big step towards truth and reconciliation. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada – one of their calls to action is making age-appropriate mandatory courses. So, the TDSB has done that work to the extent that we can, and to see that across Ontario would be a really great step in the right direction.

As soon as the Ford government was elected in 2018, it cancelled the Indigenous curriculum writing team. This was to be a big step backwards as far the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls for action were concerned. Can you comment on that?

IS: It was unfortunate to see, but there have also been steps – I believe a year ago, there was an announcement by  the Minister of Education with Native Child and Family Services, embedding Indigenous education in the curriculum. I don’t know who was in the writing team specifically, but it’s important that Indigenous people guide Indigenous education. There have been a lot of changes to education since the government took office and some have been rather unfortunate. But I think change is coming, change is inevitable and I’m looking forward to the day where we’ll have a strengthened public education system that’s stronger than ever.

the Minister of Education with Native Child and Family Services, embedding Indigenous education in the curriculum. I don’t know who was in the writing team specifically, but it’s important that Indigenous people guide Indigenous education. There have been a lot of changes to education since the government took office and some have been rather unfortunate. But I think change is coming, change is inevitable and I’m looking forward to the day where we’ll have a strengthened public education system that’s stronger than ever.

If you don’t mind, would you talk about your background as a young Indigenous man? How has it informed the approach that you take dealing with issues like this course and politics overall as a student trustee?

IS: I think it’s everything. Our lived experiences and identities influence much of how we interact with the world and, being in this position, I’ve had to rely on my own lived experiences and what I know needs to change – and the lived experiences of other Indigenous youth. I’m Mi’kmaq, as I’ve said, and I’m from Newfoundland – so it’s a little different than here. In an urban setting especially, it’s unlike being on a reserve or in a more rural community. So, my lived experience shapes everything that I do while understanding I have the privilege of going to the Toronto District School Board, being in this position, living in an urban setting. So, it’s definitely a fine line of taking my lived experiences, listening to others, taking a step back when I need to.

When did you move from Newfoundland?

IS: About 15 years ago

You were a young kid.

IS: About 3 or 4

It sounds like you might have absorbed the change a little easier than say if you were 12 or 13.

IS: Definitely – I definitely absorbed the change easier, but it was still a change – like living on the reserve for some time. Life is different. Life in Newfoundland is very different from Ontario. Newfoundland is a little warmer – which I do appreciate. But I think I acclimated pretty well.

What do you see in your future?

IS: Next year, I’ll be pursuing law – I’ll be getting my LLB – in law- and then a Bachelor’s degree in either human rights or sociology. Then maybe I’ll focus on treaty law, on human rights, on constitutional law in my practice. I might come back to the TDSB as a trustee, or maybe one day as the Indigenous trustee, but for now I’d like to take a step back from politics and learn some more before I’m put into a position like this again.