Black history, Black futures: What our students deserve

Oppressive governments wielding power against vulnerable people. Racist propaganda and misinformation spreading unchecked. Armed forces terrorizing Black and brown communities. This is America today, but these realities echo moments found throughout our nation’s long history.

As educators, we know that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. But memory alone is not enough. We must learn from history if we are to resist the injustices of today, reimagine what is possible, and reconstruct a more just future for our students, their families, and communities. That’s why we’re launching “Lessons for Resistance,” a series that taps into the wealth of knowledge that CTU educators carry: insights into how communities have confronted tyranny before, and how they have organized, survived, and won.

This is a decisive moment in our city and nation’s history, and we have a responsibility as unionists, as educators, and as people who love children to ground ourselves in the lessons of those who came before us, as we fight for the future our students deserve.

We kick off the Lessons for Resistance series with a Black History Month lesson from CTU member and Kenwood social studies teacher, William Weaver, NBCT.

Teachers across the country are grappling with how to educate students who are grappling with the realities that many of their communities have never been afforded the promise of the American Dream. Students are keenly aware of the world they are inheriting, and it is long past time that we, as teachers, provide them with historical context that emphasizes continuity rather than isolation. Many students already recognize the conditions that precipitated the rise of protest movements like the Black Panther Party: persistent disparities in their communities, over-policing, housing insecurity, limited access to healthy food, and, most critically, the unequal distribution of resources to public schools.

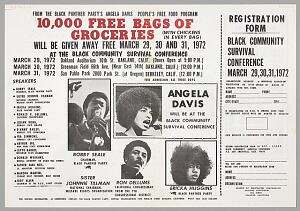

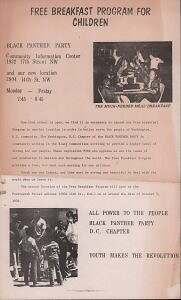

Too often, the Black Panther Party appears in classrooms only through surface-level discussions of resistance or through pop culture portrayals that reduce the organization to its visual symbolism—black berets, leather jackets, firearms, and a militant image. When taught honestly and in depth, however, students encounter something far more complex and relevant. They see a grassroots organization responding to systemic inequality through community organizing, political education, and resistance to state power. This narrative resonates deeply with students, particularly when they are asked to analyze primary sources and engage with the language of social justice that the Panthers used to mobilize communities while also confronting the internal tensions and contradictions in a society that often resists change. With that, students learn how the Panthers created the Free Breakfast for Children Program, established community health clinics, and implemented political education classes that emphasized collective responsibility and youth leadership. When students examine the Ten-Point Program and recognize that a group of young Black activists fed thousands of children years before the federal government expanded school lunch programs, they begin to ask critical civic minded questions: What role should the government play in meeting community needs? Who is labeled “radical,” and why? How do we see the movement playing out in our own communities today?

organization to its visual symbolism—black berets, leather jackets, firearms, and a militant image. When taught honestly and in depth, however, students encounter something far more complex and relevant. They see a grassroots organization responding to systemic inequality through community organizing, political education, and resistance to state power. This narrative resonates deeply with students, particularly when they are asked to analyze primary sources and engage with the language of social justice that the Panthers used to mobilize communities while also confronting the internal tensions and contradictions in a society that often resists change. With that, students learn how the Panthers created the Free Breakfast for Children Program, established community health clinics, and implemented political education classes that emphasized collective responsibility and youth leadership. When students examine the Ten-Point Program and recognize that a group of young Black activists fed thousands of children years before the federal government expanded school lunch programs, they begin to ask critical civic minded questions: What role should the government play in meeting community needs? Who is labeled “radical,” and why? How do we see the movement playing out in our own communities today?

Teaching the history of the Black Panther Party also allows students to practice essential historical thinking skills, including sourcing, contextualization, and perspective-taking, while engaging with enduring civic questions. Through these skills, students come to understand how power shapes historical narratives—whether through FBI surveillance, media portrayals, or government repression of the Panthers’ constitutional right to protest. These conversations are not unfamiliar to students who have come of age in a world shaped by record breaking protest movements and diverse forms of resistance. Rather than distancing students from the curriculum, this approach affirms their lived experiences and invites them to see history as a tool for understanding the relevant ideas of the past and the present.