Education minister thinks out loud: “less money, bigger classes” – hmmm

Let’s start with some basic information. According to the current rules, girls and boys may be in junior or senior kindergarten classes with a maximum of 29 students in them. If that class has more than 15 students, a teacher works with a qualified early childhood educator or ECE.

The class size limit for students in grades one through three is 23, although Ministry regulation 132/12 governing class size stipulates that 90 percent of primary classes in a school board must be capped at 20.

Class sizes were last reported for the 2017 -18 school year. That year 96 percent of TDSB and 90 percent Toronto Catholic Board primary classes had 20 or fewer kids in them.

Beware of Tories thinking

Now, along comes Minister of Education Lisa Thompson who announces that it’s time to think about class sizes and, by-the-way how we hire teachers in Ontario. She’s already whispered in our ears that the Doug Ford government wants to cut $1 billion dollars from education. Maybe this is one easy way to do that. In a so-called Class Size Engagement Guide, Ms. Thompson pretty much sets the government train on the “let’s cut education” track.

She asks for example “should the regulation continue to set hard caps on class sizes?” This simply means: should we open up classes to be whatever size the government wants them to be? Since she’s not laying out any limits here, class sizes in primary grades could go back up to 30 or more. Kindergarten classes could do the same.

Just to make sure we get the picture, she goes on to ask “if hard caps were to be removed from regulation, what would be an appropriate mechanism to set effective class sizes?” She might as well ask “if I happen to steal your car, what new colour should I paint it?” Given the trouble previous Ministers have taken to lowering class sizes, it makes the question of how to undo that work, all the more astounding.

And she’s not done. Ms. Thompson goes on to ask whether having an ECE in the kindergarten classes is good “value for money.”

Or maybe we should think about class sizes in general from kindergarten right the way through to grade 12. She mentions class sizes ranging from 20 students in Belgium and Finland, all the way to 40 in Vietnam, China and Turkey, then adds that “the relatively larger classroom sizes in Asian countries and their high average student performance is often cited as an example that higher performance is possible in larger classrooms.”

She doesn’t back up this claim with any information at all. But you don’t need to do that in a Ford government. Just saying it is enough.

Take China for instance, a vast country, with wide ranging population differences between rural and urban areas. Average class sizes there tend to be about 49, but could actually be as high as 80 to 100, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Its culture, economy and government are completely different. So, it’s certainly not comparable to Ontario.

What about Singapore? Maybe this is the place Ms. Thompson was dreaming about when she said that places with large class sizes might do better than others. In 2015, it outperformed the rest of the world in an international study of science reading and mathematics. But large-scale testing has enormous problems of accuracy and consistency. Using it to compare populations from assorted countries with different curricula, economies and approaches to education yields supposition – not good information. Even so, other top countries included Estonia, which has one of the lowest average class sizes in the world, and Canada. So, if Minister Thompson wants to use spurious information to support larger classroom sizes, she should at least get it right.

Singapore has average class sizes ranging from 29 to 35 students. There are 6 years of compulsory education beginning at age 7, according to OECD. Singapore has roughly 1 300 private schools That’s a lot for a population of 5.6 million. With a population of 14.9 million, Ontario has 900 of them. So, let’s just forget about comparing test scores as a reason for increasing class sizes.

Playing with blocks

The Ford government acts as though education is as simple as a set of Lego blocks with pieces that can be rearranged to make it cheaper. But as David Zyngier, an Education professor at Monash University in Australia, says in a 2014 article “…an educational system forms a working whole, each component interacting with all other components. Isolating any one component (such as class size) and transplanting it into a different system shows a deep misunderstanding of how educational systems work.” That misunderstanding should be interpreted as cynicism here, as our government guts curriculum, local spending, early childhood education, income supports and all those components that interact with one another to produce learning – or not.

The Ford government acts as though education is as simple as a set of Lego blocks with pieces that can be rearranged to make it cheaper. But as David Zyngier, an Education professor at Monash University in Australia, says in a 2014 article “…an educational system forms a working whole, each component interacting with all other components. Isolating any one component (such as class size) and transplanting it into a different system shows a deep misunderstanding of how educational systems work.” That misunderstanding should be interpreted as cynicism here, as our government guts curriculum, local spending, early childhood education, income supports and all those components that interact with one another to produce learning – or not.

Contrary to the Minister of Education, he argues that increasing class size not only hampers students’ academic results in the short term but also success in the long term, adding “Money saved by not decreasing class sizes may result in substantial social and education costs in the future.” This too sounds familiar as we watch a government do all it can to kick problems down the road.

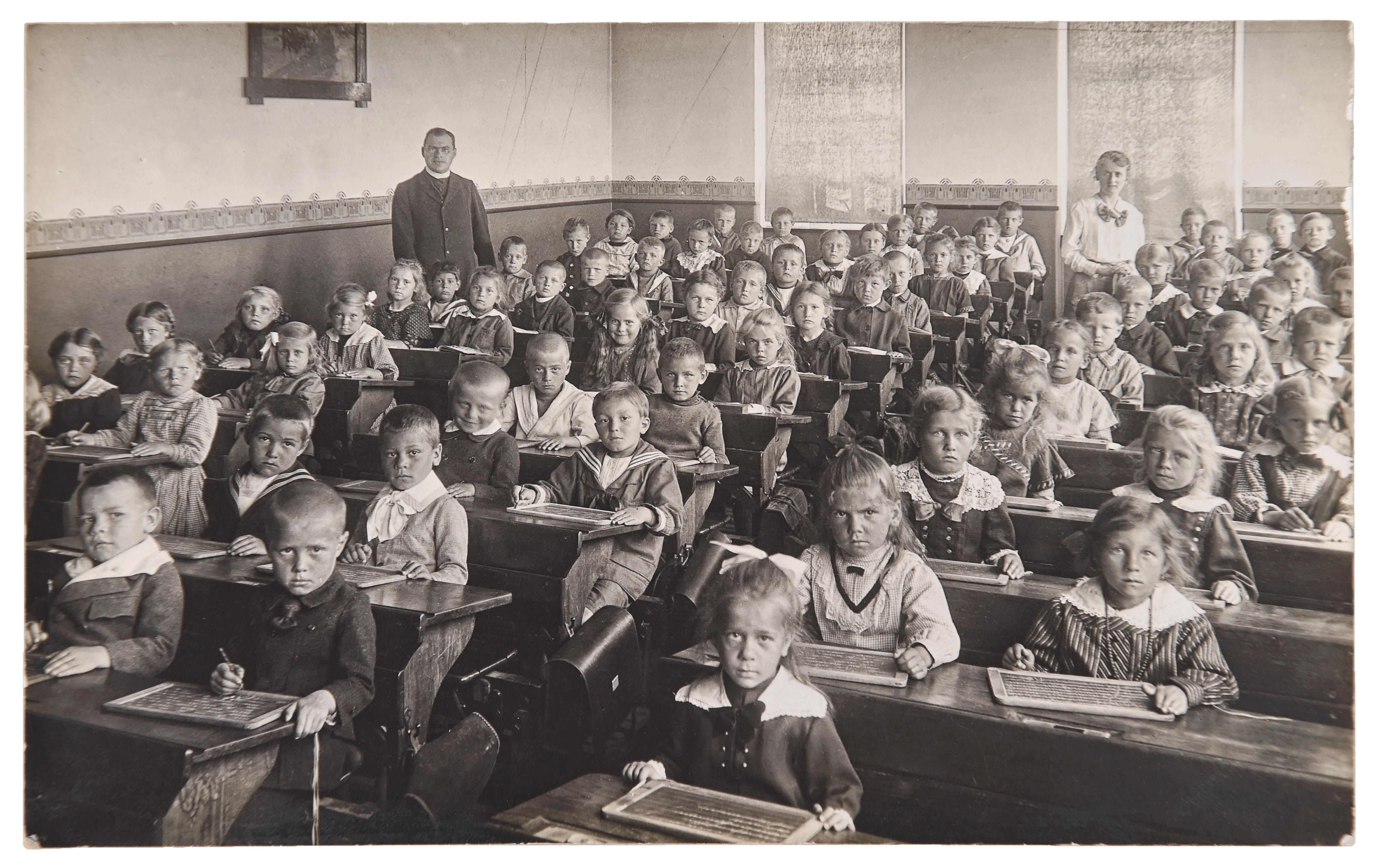

The good old days

Ontario schools did indeed once have larger class sizes – 35 and up a few generations ago. But children sat in desks that were organized in rows, were not allowed leave them without permission, always had to raise their hands when they wanted to say something and Heaven forbid that they got caught talking with their neighbours. If some children didn’t “get” the curriculum one year, they just repeated the year. Discipline not management techniques were the order of the day and anyone who went to school under that regimen of learning surely can remember writing lines: “I will not speak out in class” or something of that sort.

Fortunately, things have improved. Teaching practice, unless the Tories change it, has for years moved to comprehend a student in the world he or she inhabits. Good teachers understand the neighbourhood around the school – its economy, social conditions and the stresses that come with these things. They understand that one child needs a bit of space to move around, that another is motivated by science experiments, yet another needs more help than the classroom can provide; and so it goes. It all changes from school to school, board to board.

Of course, smaller class sizes make the work of teachers more effective.

And let’s not forget the demands upon teachers now. In the days of large class sizes, school populations were more homogenous. Teachers didn’t have to consider the widely varied needs of children coming to their class from different countries and circumstances. Kids with special needs might be bused to self-contained special education classes in another school. Government policy today is integration of those young people into regular classes at their home schools, despite how remarkably different they might be in the way they learn. There are no guarantees that these kids will be adequately supported in the regular class. Nonetheless, their teachers need to teach them.

Education on the cheap

It looks like Ms. Thompson is asking: why not have it both ways? Why not increase the expectations on teachers to cope with problems in their classes they didn’t need to address 20 years ago, handle the higher expectations of parents who consider fairness and equity to be important – and then just increase the number of children they have to teach?

NDP education critic, Marit Stiles thinks the Ford government is making the calculation that people are more concerned with health care than education. So, make cuts in education and whittle down health.

It’s a perfect storm created by a government that doesn’t count vulnerable people among its friends. Schools have been struggling for more than 20 years with poor funding, decrepit schools and increasing expectations. This government will add another few blocks to that load, watch it collapse, then offer privatized solutions or “choices” as Ms. Thompson likes to call them.