From the picket line – another week in the life of a strike

PCs plan – people push back

The Rainbow Motor Inn is like a lot of old tourist spots in Niagara Falls. It looks like it was built in the early ‘60s – the familiar two-story L- shape on ½ an acre with a swimming pool in one corner. It’s right near the corner of Murray St and Stanley Ave. There’s a Tim Horton’s beside it and on the old sign outside the motel office, it says “near the Falls.” That doesn’t make much difference nowadays; it sits in the shadow of the giant Hilton and Radisson Hotels, the Embassy Suites and the Fallsview Casino; none of them were there when the Rainbow Motor Inn went up. Now it offers $10 parking spaces for people who want to go elsewhere and waits it’s turn to become a chain restaurant or part of a larger parcel that will make up another massive building.

Like the Scotiabank Convention Centre a little further down Stanley Ave – a more appropriate spot for the PC Ontario Policy Convention.

Talk about contrasts. Inside the huge plate glass windows, it was easy to see Tory members ambling about, chatting with one another between policy sessions, seemingly oblivious to the rest of us on the outside looking in. It seemed quiet; peaceful in that featureless way that marks the architectural style of convention centres.

Talk about contrasts. Inside the huge plate glass windows, it was easy to see Tory members ambling about, chatting with one another between policy sessions, seemingly oblivious to the rest of us on the outside looking in. It seemed quiet; peaceful in that featureless way that marks the architectural style of convention centres.

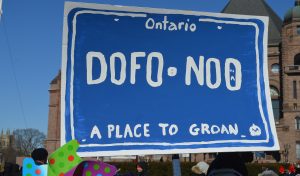

Outside was a different story. Stanley Ave, in the block outside the convention centre, was filled with a thousand union members, retired union members, teachers, early childhood educators, parents, parents of kids on the autism spectrum, nurses and members of health care coalitions. The flags alone, told a story: OSSTF, ETFO, OECTA, AEFO and that was just the educators. Joining and supporting them were the Labourers International Union of North America (LiUNA), Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) United Steel Workers (USW), United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Unifor, Communists, Ontario Nurses Association (ONA), Canadian Auto Workers and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

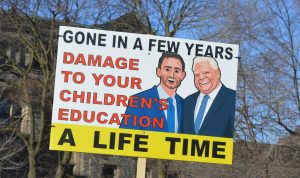

It was a noisy jumble of people worried about and furious with the policy makers inside. Patty Coates, President of the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL) – the organizer of the rally- told me that the “majority of Ontarians are not happy with the cuts of the PC government,” adding that Tory politicians “need to change their direction or they’re going to be gone.” She was quick to point out that this demonstration was about education – but more than that: parents of autistic kids, working families, health care supporters – so many others who have felt the bite of Doug Ford’s policies.

President of the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL) – the organizer of the rally- told me that the “majority of Ontarians are not happy with the cuts of the PC government,” adding that Tory politicians “need to change their direction or they’re going to be gone.” She was quick to point out that this demonstration was about education – but more than that: parents of autistic kids, working families, health care supporters – so many others who have felt the bite of Doug Ford’s policies.

Educators are currently carrying the ball with strikes across the province, but there’s much more to bind people together. A steelworker said that “we’re here to get rid of Doug Ford…we all have to pull on the same rope in the same direction.” Crystal Sinclair, of Idle No More Toronto, was there to highlight the blockades across the country over the Coastal Gas pipeline in Wet’suwet’en Territory in BC. Noting Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s call to remove the rail blockades she insisted, “Indigenous people are not be moved from their land.” Lena Sutton, a retired local president for USW, told me, “we’re disgusted; cuts hurt everyone; long term care, education, hospital wait times.” Natalie Mehra of the Toronto Health Coalition explained that the demonstration was for all community members protesting cuts to all social services – against a government that would cut residential addiction treatment programs and public health. Kayla Wyler of the Canadian Federation of Students reminded everyone of the $670 million cut to the Ontario Student Awards Program, adding that it’s worse than it first seems “because we still haven’t recovered from two decades of cuts.

There was a lot of encouraging talk about a larger, broader fight against the Ford government. Liz Stuart, president of OECTA told the people on the outside of the convention centre “next comes health care, next comes all our other public services if we don’t stand up now and push back.” OSSTF president Harvey Bischoff was speaking to more than just teachers as he said: “We fight for dignity of work and we fight for dignity after work. And we fight to have an educated citizenry that can push back against the elite that want to push us around and manipulate us.” Sam Hammond of ETFO told the crowd, “… this is just the beginning. And you know they are coming after us or attacking us and my friends, make no mistake, make absolutely no mistake – you’re next. So, this is a much bigger fight.” OFL President Patty Coates underlined the point: “If the Conservatives don’t listen to us…we will shut this province down.”

There was a lot of encouraging talk about a larger, broader fight against the Ford government. Liz Stuart, president of OECTA told the people on the outside of the convention centre “next comes health care, next comes all our other public services if we don’t stand up now and push back.” OSSTF president Harvey Bischoff was speaking to more than just teachers as he said: “We fight for dignity of work and we fight for dignity after work. And we fight to have an educated citizenry that can push back against the elite that want to push us around and manipulate us.” Sam Hammond of ETFO told the crowd, “… this is just the beginning. And you know they are coming after us or attacking us and my friends, make no mistake, make absolutely no mistake – you’re next. So, this is a much bigger fight.” OFL President Patty Coates underlined the point: “If the Conservatives don’t listen to us…we will shut this province down.”

But how will this come out? CUPE President Fred Hahn steered away from the question of a general strike across the province, but told me that unions need to mobilize everywhere and engage people in communities, rallies and so on. Wayne Gates NDP MPP for Niagara Falls declared: “This is a united front with labour with community and that’s how we’re going to defeat this government.”

On the other side of the glass, Premier Doug Ford was planning for more of the same, proclaiming to convention delegates: “Absolutely nothing and I mean nothing is going to stop us.”

Nothing maybe, but a well-organized common front of educators, health workers, public service workers, parents, students and the rest of the union members in Ontario who think this Ford belongs in the parking lot of an old motel.

200 000 educators on the picket lines

From MacLean’s Magazine November 10, 1997 by Mary Janigan and Anthony Wilson Smith

For both short and long-term reasons, the stakes are enormous. The immediate concern last week was the effect that a prolonged strike would have on students. Then there was the fate of the teachers, who faced either the pressure of staying off the job or submission to a series of changes they say would radically alter their workplace and their bargaining power. Whatever their decision, tempers were likely to remain high. As Eileen Lennon, president of the Ontario Teachers’ Federation, vowed: “As long as Bill 160 is on the table, teachers will be fighting it.”

On the government side, the stakes may be even higher. Harris is determined to pare an additional $500 million to $667 million from the education system’s $14 billion price tag. And as a former teacher and school board trustee, the premier is firmly resolved to overhaul a system that he depicts as inefficient, outdated—and too decentralized to ensure curriculum quality, smaller classes or value for taxpayer money. The current legislation would remove school boards’ rights to negotiate key contract conditions, such as teachers’ preparation time. It would also allow the province to use individuals who do not have teaching certificates for certain classes, to expand classroom time and to increase the number of instructional days in the school year. The teachers argue that the government wants to increase their work load because it is determined to save money—at the expense of educational quality.

In 1997, teachers walked out over Bill 160, the perversely named Education Quality Improvement Act, that centralized power in the Ministry of Education, reduced school boards to the role of functionaries, taking away their authority to bargain over teachers’ working conditions. The province had already cut $1 billion from education, but wanted more. The result of Bill 160 was over two decades of fighting over a funding formula that has never worked, decaying schools, a corporate pedagogy based on outcomes and an Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) that, out of the blue, plans to test teacher candidates because the premier says they can’t do Math.

In 1997, teachers walked out over Bill 160, the perversely named Education Quality Improvement Act, that centralized power in the Ministry of Education, reduced school boards to the role of functionaries, taking away their authority to bargain over teachers’ working conditions. The province had already cut $1 billion from education, but wanted more. The result of Bill 160 was over two decades of fighting over a funding formula that has never worked, decaying schools, a corporate pedagogy based on outcomes and an Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) that, out of the blue, plans to test teacher candidates because the premier says they can’t do Math.

It’s important to look at Friday’s walkout of 200 000 teachers in this light. Thirty thousand of them alone filled Queen’s Park Circle. Thousands more from Peel lined Hurontario Street in Mississauga. All educators were out, everywhere across the province.

The issues are fundamentally the same as the last time the Tories used a hammer to fix education.  The problem is that subsequent Liberal governments never really addressed them – centralization, funding, repair and renewal of buildings, absurd high stakes tests and a direction in the philosophy of teaching that put finished student product far ahead of the process of teaching her.

The problem is that subsequent Liberal governments never really addressed them – centralization, funding, repair and renewal of buildings, absurd high stakes tests and a direction in the philosophy of teaching that put finished student product far ahead of the process of teaching her.

When Doug Ford, with no education experience, but a desire to cut 4 percent from the budget, came long and declared education broken, everyone who cared about it, knew what was about to happen. There would be cuts and they would be massive and, in keeping with the production-line thinking of the Tories, why have more teachers when computers will do?

Despite Education Minister Stephen Lecce’s nonsense to the contrary, this series of strikes by educators of all kinds has been not about wage increases or Regulation 274 (fair hiring practices), but about trying to claw a way out of that hole dug in 1997. Over and over, teachers I spoke to told similar stories. A grade 6 teacher from Essex County told me that class size is on top of the list of demands, “but it’s become evident that we need supports to keep kids safe. The EAs (education assistants) are my safety belt.”

Many people – parents and educators –worried about the integrated special education model that’s  becoming increasingly popular as resources are stretched. The philosophy, such as it is, goes: “It makes students feel unsuccessful if they have to leave the regular classroom to get extra help, so this help should be given in the classroom.” A lot of the time that might work, but you have to have trained people to provide the help. That’s not happening, because budgets have been cut. Teachers, with or without special education training, deal with more needy students on their own- students who may not take well to embarrassment of not being able to keep up in class and act out.

becoming increasingly popular as resources are stretched. The philosophy, such as it is, goes: “It makes students feel unsuccessful if they have to leave the regular classroom to get extra help, so this help should be given in the classroom.” A lot of the time that might work, but you have to have trained people to provide the help. That’s not happening, because budgets have been cut. Teachers, with or without special education training, deal with more needy students on their own- students who may not take well to embarrassment of not being able to keep up in class and act out.

A speech and language pathologist picketing Queen’s Park on Friday explained that integration may not work for everybody; some kids need a quieter setting with someone trained to help them with a very specific problem. But if you’re going to integrate students, you can’t cut people with training like hers from school boards and expect much for students in the regular class.

Another teacher explained how, years ago, he’d taught a junior level class of 42 but that it was the changed special education model that has made teaching untenable – and no Home School Comprehensive teacher to work with kids with challenging learning or social problems. Another pointed out that, with 30 students in the class, integrated special needs kids get maybe a couple of minutes of his time. Educators and parents love to talk about kids and go on at length about what’s needed to support them.

No one, at Queen’s Park or any of the other pickets I’ve attended since December, has shown more than a mild interest in wages and benefits. One teacher had forgotten what regulation 274 was about. These people see a bigger picture and regressive cuts and pedagogy like e-learning are not in it.

Friends of public education set up Solidarity Camps

What to do? You’re a parent and see the effects, first hand, of the cuts the Ford government is making to your school – fewer caretakers, fewer teachers and education assistants, larger classes and more kids who need a lot of help. Doug Ford is saying it’s the fault of the Liberals, the teachers, their unions, everyone’s demands. But it doesn’t add up; he’s crying poor at the same time he’s lowering taxes and giving up income from the cap and trade program.

You support teachers just as much as you see the ominous signs of a government planning more cuts. But there’s this strike and everyday your kids are out of school it could cost you – days off work or extra child care expenses. If you’re not making high wages or if you’re a single parent, it just gets harder.

You support teachers just as much as you see the ominous signs of a government planning more cuts. But there’s this strike and everyday your kids are out of school it could cost you – days off work or extra child care expenses. If you’re not making high wages or if you’re a single parent, it just gets harder.

That’s what Minister of Education, Stephen Lecce is counting on. It’s a cudgel he can use against educators: they’re abandoning the “little guy” as his boss likes to call Ontarians who aren’t like him – portraying poor working people up against those big teachers’ unions. Time and again, when he’s not saying that educators are only interested in more money, he’s saying that working families are being shafted. It’s the old tactic: divide and conquer.

Thanks to groups like Ontario Parent Action Network (OPAN) you can get help with child care. OPAN got its start in the west end of Toronto. Members realized that the idea of parent action for education resonated with a lot of people all over the city and the rest of the province. It organized and participated in many of the 750 walk-ins to schools over the past year and has connected with parents in Peel, Kitchener-Waterloo and as far away as Ottawa.

During the past 4 weeks of educators strikes it’s run Solidarity Camps offering free or very low-cost ($10 – $15 per day) child care for parents who need it. According to OPAN organizer, Rachel Huot, Solidarity Camps have sprung up across the city in Parkdale, the Coxwell and Gerrard area, near Dundas and Jane streets, Regent Park as well as at Bloor and Bathurst and the Rockcliffe-Smythe Park area in the city’s west end. Organizers set them up in churches and legion halls and community centres.

Ms. Huot says that while OPAN co-ordinates and helps organize Solidarity Camps, the real work is done by parents, volunteers and even educators after they’ve finished their picket duty on a strike day.

This is a model worth developing. It doesn’t dilute the effect of educators going on strike; it just makes it less onerous for lower income parents. As Rachel Huot points out, Solidarity Camps are “what it looks like for parents, teachers and education workers to work in solidarity.”