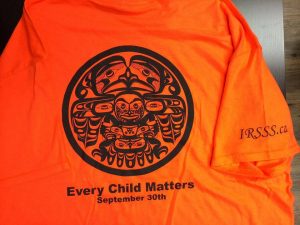

Orange and reconciliation: orange shirt day

Phyllis’ story

Phyllis Webstad is Northern Secwpemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation. She has a son, a step-son and five grandchildren. She is also the Executive Director of the Orange Shirt Society and author of two books: the “Orange Shirt Story” and “Phyllis’ Orange Shirt”

It’s her story that gives the name to Orange Shirt Day on September 30. Hundreds of thousands of kids across Canada have observed it since 2013 to honour residential school children, their families and communities. These were the over 150 000 Metis, Inuit and First Nations children taken from their families, not for education, but simply to break their links to their homes, their identity and their culture.

It’s her story that gives the name to Orange Shirt Day on September 30. Hundreds of thousands of kids across Canada have observed it since 2013 to honour residential school children, their families and communities. These were the over 150 000 Metis, Inuit and First Nations children taken from their families, not for education, but simply to break their links to their homes, their identity and their culture.

As Canada’s first Prime Minister, John A Macdonald told the House of Commons in 1883

“When the school is on the reserve the child resides with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simple a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.” (sic)

Phyllis Webstad had just turned 6 in 1973 and, like all kids, she was excited about her first day at school. She lived with her grandmother on the Dog Creek reserve in BC and picked out a new orange shirt to wear for the occasion. When she arrived at the St. Joseph Mission residential school in Williams Lake BC, it was different story: “they stripped me, and took away my clothes, including the orange shirt! I never wore it again. I didn’t understand why they wouldn’t give it back to me, it was mine.” The orange colour of the shirt was a reminder of how “my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing.”

Looking at history

Orange is a colour that caught on, that represents the thousands of Residential School Survivors who were brutalized in a diligent historical effort to “kill the Indian in the child”, as former Prime Minister Stephen Harper said in 2008. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported, in 2015, Canadian governments after Confederation simply took over control of First Nations lands, forced their people to accept treaties “often marked by fraud and coercion”, the provisions of which “Canada was and remains slow to implement.” Just think of over 100 First Nations communities currently without clean drinking water.

Schools, to educators’ despair, were at the heart of this culturally genocidal plan: from Macdonald’s time through Phyllis Webstad’s experience, right up to 1986 when the last residential school finally closed its doors. These schools embodied a perversion of what educators want for students. It wasn’t education that led leaders of government and Canada’s churches to separate Indigenous brothers and sisters, cut off their hair, forbid them to speak their own language or practice any aspect of their culture or faith.

It wasn’t for education that Indigenous children inherited a legacy of pain and suffering for generations. Living conditions at these schools were dreadful. Poor sanitation, inadequate food and health care lead to disgustingly high death rates of 24 percent by 1907. Children, unprotected by their families , were subjected to severe corporal punishment, assault and rape. As recently as 2005, Arthur Plint a dorm supervisor at the “Port Alberni Indian Residential School” was convicted of 16 counts of sexual assault. BC Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called Plint a “sexual terrorist” adding that as far as he was concerned the residential school system “was nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia.”

, were subjected to severe corporal punishment, assault and rape. As recently as 2005, Arthur Plint a dorm supervisor at the “Port Alberni Indian Residential School” was convicted of 16 counts of sexual assault. BC Supreme Court Justice Douglas Hogarth called Plint a “sexual terrorist” adding that as far as he was concerned the residential school system “was nothing more than institutionalized pedophilia.”

Education and reconciliation

But it is education that can help to bring about reconciliation despite governments’ efforts to avoid history. The Wynne government made a start before it was defeated in 2018, adding curriculum that gave as much weight to Indigenous culture and daily life, for example, as that of European colonizers. Important too was a question for teachers to ask: “Why did the residential school system meet with growing resistance from Indigenous families during this period? What happened when some parents resisted the removal of their children?”

The Ford government put an end to the next phase of curriculum writing when it cancelled meetings with Indigenous educators and elders right after it came into office.

Fortunately, educators need not – actually should not – rely on the blessing of any government to teach history. They take on this task armed with the charge to young people of Justice Murray Sinclair, Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

“You must watch, you must listen and you must show respect.”

Here are some resources for Orange Shirt Day and beyond:

From Orange Shirt Day website:

From Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario (ETFO)

-

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation. Where Are The Children?

- British Columbia Teacher Federation. Gladys We Never Knew.

- Canadian Teachers’ Federation. Speak Truth To Power Canada: Defenders for Human Rights.

- Manitoba Teachers’ Society. Secret Path Lesson Plans.

- Ontario Teachers’ Federation. Useful Links for Aboriginal Education.

- Secret Path by Gord Downie. Video and Resources.

From National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

From CBC kids