Public Education Not Privatization – The LA Teachers Strike

Teachers across the United States have been on strike this past year –in red states and blue – from West Virginia, Arizona, Kentucky, Colorado, North Carolina to California.

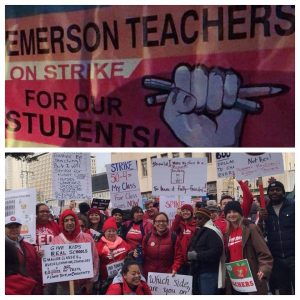

In Los Angeles, thirty-one thousand educators with United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) went out on a 6-day strike on January 14, this year. The strike wasn’t just about wages and working conditions but about teachers and education workers demanding better education and conditions for their kids and communities. They didn’t go out alone. They had support from communities, parents and students.

Teaching in LA

Noriko Nakada teaches grade 8 English to kids in middle school. Her school is in the Westwood area of Los Angeles, pretty diverse she says with mostly Latino kids. Her classes have 40 students in them, but there’s a nice school culture there, not a lot of discipline issues. Still, settling that many kids into class takes a long time. There’s not the time she needs to grade as many papers and give students individual attention. Students have a wide range of reading skills in Ms. Nakada’s classes, so English teaching centers on reading fluency not comprehension, discussing ideas or integrating them with other literature.

Large classes are typical in Los Angeles public schools, she says. After grade 3, classes tend to have more than 30 kids in them. In high schools they can run as high as 50. Her school also deals with the kids who need more attention, since privately-run charter schools don’t have to take them in. For students learning English for the first time, kids who need special education, there just isn’t the time to help them.

Once a week the principal or one of the vice-principals, conducts random searches of boys and girls in Ms. Nakada’s middle school. They go through backpacks and run wand-type metal detectors around them looking for weapons. They never find anything, she says and it’s not all that random, since it’s mostly non-white students who are chosen- whose parents don’t have much power and might not be so quick to raise a fuss.

Austerity measures hit LA schools in 2008 with mass lay-offs of teachers. Since then more teachers received pink slips as enrolment in public schools fell. In her school it’s gone from 1 500 to 600 students today. It has lost custodians and guidance counsellors. In an area without socialized health care, there’s only enough money for a nurse to come in once a week. There is no librarian in the school.

In January, Noriko Nakada did something unique. She joined 31 000 other teachers, counsellors and librarians on the picket line to demand better education for the 640 000 students in Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). After 23 years teaching and two young children starting out in school, she says, “the way we’re funding our schools and running our schools is not working for kids”

For themselves, teachers won a 6 percent wage increase to barely keep up with the cost of living. But the strike was really about something historic – the need to return schools to being places of learning, where students get the attention they need in smaller classes, with nurses, librarians and counsellors to support them. Places where poorer or racialized children are not subject to random searches by police and administrators; schools that do not need to compete with privately run – but publicly-funded charter schools.

At the centre of all of this is the powerful idea of the community school and what it can offer to neighbourhoods and the people who live in them.

It’s a story for all of us here in the land of Doug Ford’s Tories, who have taken a page out of the California no tax- no spend playbook.

Listen up, Ontario.

California schools

What’s going on here? In a state boasting the most billionaires anywhere in the world, the centre of arts and entertainment, high tech – a bastion of American liberal ideas, you have stunning inequality and poverty. The school districts across California reflect that.

In Los Angeles, schools contend with overcrowded classrooms – up to 55 students per teacher in high schools- and few resources to help them. According to a recent Guardian article, in poorer sections of the city like South LA or the northeastern San Fernando Valley, libraries are rarely open. Janitors are in short supply. Teachers spend their money on cleaning supplies to go over their classrooms at the end of the day.

Much of the decline in schools across the state accompanied a populist referendum back in 1978 called Proposition 13. It rings familiar in today’s Ontario. Proposition 13 presented a simple solution to high inflation of the 1970s: just wipe out so-called reckless public spending. To this day, it requires a 2/3 majority of California’s legislature to increase tax rates or revenues; the same is true for local governments. As its sponsor, businessman Howard Jarvis said at the time: “The most important thing in this country is not the school system, nor the police department, nor the fire department. The right to have property in this country, the right to have a home in this country, that’s important.”

In the blink of an eye public funding for education was cut by a third with no chance for recovery due to caps Proposition 13 placed on collecting revenue. Local property tax revenue dropped by 60 per cent. The state stepped in to cushion the blow, but the effects were immediate. Summer school and adult education went out the door along with vocational education, guidance, assistant principals, maintenance and librarians. After school programs ended, so did dance, arts programs and even field trips

At the same time, California’s Supreme Court ruled that the state government needed to control spending by school districts because there was so much disparity between wealthy and poorer areas. This was at a time when up to 60 percent of local school funding came from local governments. Across the state, cities had better schools than rural areas, affluent white suburbs were far better able to provide a decent education than black and Latino neighbourhoods where students faced curfews rather than well-funded schools. Areas like Beverley Hills could use their vastly greater resources to put out $1 231 per child – and this was back in the 1960s – while the Baldwin Park Unified District in LA County had only $577 in its collective pocket for each student.

You might think that the California Supreme Court ruling would help to even out the inequities, but spending levelled down not up. Adjusted for inflation, in 1977 California spent on average $1 000 more per student than other districts across the U.S. By 1983 that number was below the national average – and it’s stayed there according to the National Centre for Education Statistics (NCES) . As of 2015, the California Budget and Policy Centre ranked the state’s spending per student as 41st in the nation.

At the same time, with its reduced revenues, California did not redirect funds to needier neighbourhoods, but increased the pupil to teacher ratio. Like Ontario, voters elect local school boards to run their schools – but with no power to tax. School financing is centralized. Coping with the problems that come from not having enough of it, are local.

In an October 2018 report the American Institute for Research (AIR) estimates that California needs to spend an additional $25.6 billion over its current $66.7 billion budget to meet its goals of preparing kids for their needs in the 21stcentury.

People with money over the years have found different solutions for poorly-funded schools. Some financially supported local schools, pushed for voluntary taxes and opened charter schools. Today even within Los Angeles, you see schools like Palisades High, a charter school with its variety of clubs and student unions striking a sharp contrast to South LA’s Manual Arts High where merit awards are given out for showing up to class. As school declined in the 70’s and 80’s parents who could afford it, put their children into private schools. Between 1970 and 1990 private school enrollments increased from 14 to 21 percent among the most affluent people in the state. As recently as 2016 7.4 percent of California students attended private schools.

In light of the Ford government’s musings about increasing competition between service agencies, it’s worth having a closer look at the role charter schools play in this story. There are currently 277 charter schools in Los Angeles attended by about 154 000 students. They receive funding based on the same formula as public schools. Unlike public schools run by an elected school board, most charters are independent, run by organizations with self-appointed boards. They do not have to follow most state regulations and may operate under their own goals and procedures. Charters have been allowed to operate for the past twenty years in California because they’re said to be more flexible in curriculum, management and hiring practices. Teachers at charter schools do not belong to unions.

They are also heavily backed by private money and highly political. A 2015 article in the LA Times reported that real estate and insurance billionaire Eli Broad’s foundation for example put $490 million into a plan to enroll half of Los Angeles’ students in charter schools by 2023. Eli Broad has already invested $144 million in charters. Last April, he donated $1.5 million to a pro-charter school group supporting former LA mayor Antonio Villaraigosa’s run for state governor. The group, Families and Teaches for Antonio Villaraigosa is sponsored by the California Charter Schools Association.

Mr. Broad was joined by Netflix chief, Reed Hastings, who pitched in $7 million to the same group. Despite the support from the charter school association, Mr. Villaraigosa wasn’t elected.

Across the U.S. charter schools have grown in number with grant support from the Obama administration, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation. Betsy DeVos, current US Education Secretary and wife of Amway founder, Dick DeVos, is a major supporter of these schools, which are able to run without the nettlesome oversight of unions and public scrutiny.

What’s important here is that charter school promoters base their support on the self-fulfilling prophecy that public schools are failing and that public money in the hands of private management is the answer to save them. Since the 1970s California public schools have declined, deprived of money from the very people who now offer choice as the solution.

Sound familiar?

Organizing

Teachers organized under United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) face tough conditions all across the city. UTLA Affiliate President Cecily Myart-Cruz told School Magazine that random searches are anything but. They happen mostly in low socio-economic schools, ones with a higher number of black and brown kids. When police, rather than administrators do the searches, they bring dogs with them and often target Muslim girls, getting them to dump their backpacks containing tampons and so on. It’s about intimidation, she says.

She adds that charter schools have grown about 200 percent since 2008, with more local public schools sharing space. The school district will give space to a charter in a public school as long as a teacher isn’t occupying it. For example, in a school that has lost a librarian, the library is now fair game for the charter to take over. The same is true for portables in the school yard, computer labs and parent centres.

Ms. Myart-Cruz maintains that of the seven school boards within the LA Unified School District, (LAUSD) only 2 are not controlled by the California Charter School Association who, not surprisingly, promote school board candidates who will push for more charters.

It took years to build a movement for public education. It also took enormous time and expertise to gather the teacher and neighbourhood support to get to the point where there was enough political power to move against the LAUSD and the powers behind it supporting the status quo. Teachers were fed up that nothing was changing. Cecily Myart-Cruz says “we knew we had to do something to start the conversation in a different way for our members.” UTLA set basic organizing principles:

- Organize collectively for educator empowerment

- Engage parents

- Don’t be afraid of the word strike if you need to call a strike.

Escalating actions

As they moved ahead UTLA organizers set goals and contract demands based on their conversations with educators. They took another step forward when it was clear they had their backing. UTLA put what it calls Action Teams at schools to contact teachers and get feedback right away. The teams tracked petitions, talked to key people and followed up.

The whole campaign was built around escalating actions: handing out flyers at schools, then picketing, then holding regional rallies, then going for a strike vote. But no next step was taken without testing the membership: Are people following up? Are they willing to take the next step? It was critical to make sure that their members had the information they needed about school conditions, the political power of the charter school lobby and so on.

Forming a coalition

But what made organizing different was that it had to be about forming a coalition with parents, students and neighbourhood members. One parent group Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools (AROS) set out its demands clearly: full funding for community schools, more teaching, less testing, positive discipline policies, quality affordable education and a living wage that lifts people out of poverty. Another, Reclaim Our Schools LA pushed for a moratorium on charter schools. UTLA also worked with Black Lives Matter LA to pressure the LAUSD to put an end to the random searches of students.

Students joined this fight. They set up groups like Students Deserve and joined with a campaign run by the National Union of Students, Students Not Suspects staging walkouts. At one point they held a meeting in a public square to demonstrate what a random search looks like. Just last month students organized a “sick out” supporting their friends in Oakland where there’s another strike looming over the same issues in Oakland. Communities and educators got together over issues that have festered for generations.

School as the neighbourhood hub

The community school is the key idea here. It starts with the fact that the local school is the hub of its community. Neighbours use it for a park, a place to gather, hold meetings. It can be a be a place where people can go for basic health care, counselling, legal advice, and more. Of course, it offers good education for the community’s children. Members of the community are making sure of that, because they’re engaged.

The community school is the key idea here. It starts with the fact that the local school is the hub of its community. Neighbours use it for a park, a place to gather, hold meetings. It can be a be a place where people can go for basic health care, counselling, legal advice, and more. Of course, it offers good education for the community’s children. Members of the community are making sure of that, because they’re engaged.

UTLA won a concession for 20 schools to be designated community schools this year and 30 more for next year. Each designated school comes with funding for a school co-ordinator, much like those we used to have in Toronto – community organizers who could link families with local politicians, social service agencies, or hold meetings to take action on some local issue. The neighbourhoods of these schools have some control over their funding. They’re located in high needs areas.

These community schools can respond to local situations that affect families, their children and learning. Is access to food and shelter a problem in one part of the city? Does the neighbourhood need a wellness centre? Does the local school need more help with homework for students? What about after school activities or even something as simple as snacks for kids waiting for their parents to get home from work?

Schools and affordable housing

You can see the community emphasis in other demands. The union pushed, though didn’t win, a proposal to sell unneeded school properties that could be used for affordable housing. It was able to get the LA District to remove unused portables from schoolyards, adding more greenspace to neighbourhoods – and incidentally, making them unavailable for charters. It even managed to get an immigrant defense fund for residents. The union and its supporters took the broad view of the community and what was needed to make it work for its schools and kids.

What about the random searches?

Not a complete victory by any means there. However, the LAUSD agreed to run a pilot program to end searches in 26 of its roughly 1000 schools. It will need a lot more pressure to give way on this key part of the school-to-prison pipeline that afflicts millions of insufficiently well-off students across the U.S.

The teacher/community alliance made some advances on other key issues too:

Class sizes from grades 4 – 12 will drop by 1 in 2019-20; and 1 more in 2020-21; 2 more in 2021-22. Grade 3 classes are to capped at 24-27 students.

The LAUSD will permanently hire 300 new nurses. It will hire 77 counsellors – bringing the student/counsellor ratio to 500:1 There will be 82 more librarians working in secondary schools.

Getting rid of privatization

And the charter schools? UTLA demanded the district vote for a resolution calling on California to put a cap on them, something they won and for which the LAUSD voted 6-1. Of course, this didn’t go over well with charter school supporters who will likely continue to use their resources to lobby both local and state governments to see that any cap or moratorium is voted down.

Cecily Myart-Cruz says that because of the strike, the idea of getting rid of privatization is now stuck in the “politicians’ brains” They see strikes across the country – Chicago, West Virginia, Kentucky, Arizona, recently in Oakland and one authorized for Sacramento – and will have to make a choice about whether to privatize or overturn measures like Proposition 13 and fund schools and all the services that hold communities together.

For now teachers like Noriko Nakada know for sure that the struggle for better schools continues. To remind themselves and their communities, every Tuesday they show up for work wearing “red for ed.”

It’s a reminder that should not be lost on those of us in Ontario who will not stand to see public education to go down Doug Ford’s rabbit hole. The only way to stop that is for educators and parents to seriously organize and form a broad and powerful coalition “for the people” that Doug Ford and his cronies do not represent.