Teaching the Radical Rosa Parks

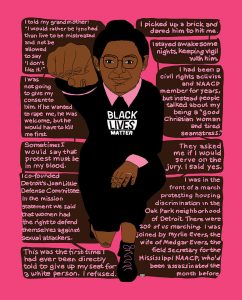

Banner illustration by Kyla Sas

Bottom illustration by Louisa Bertman

The current issue of the American magazine Rethinking Schools is devoted to “The Uprising in Our Schools.” It comes at the heels of months of protest across the continent over the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony Dade and others. It is an uprising described by Black Lives Matter at School as setting off a “Year of Purpose” during which educators should look at their work in the way it supports anti-racist pedagogy and how they can make Black lives matter in their classrooms, schools, communities and beyond. There are great articles in this issue and School urges readers to check them out and subscribe to the magazine.

One of the articles, we’re excited to republish below is Teaching the Radical Rosa Parks by Bill Bigelow. Rosa Parks is known everywhere as the African American seamstress, who, on December 1, 1955, refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery Alabama bus, to a white passenger, when ordered to do so by the bus driver. But there was so much more to her life filled with activism and resistance; so much more for educators to use to explain how their students need not be trapped by history, but can do something about it. It’s not just the history of one big step forward, but the winding, uncertain route to fairness and decency that entails.

My wife Linda and I began our COVID-19 shelter-in-place pretty early in the pandemic. I went to my last in-person meeting on Wednesday, March 11. The next day, we canceled our monthly Portland Public Schools Climate Justice Committee meeting, and from then on, life became very different.

In that early pandemic period, I felt fear, but also despair. How could we change the world when people couldn’t even sit together in the same room? Staring at computer screens of little Zoom boxes of people’s faces underscored just how isolated we were. Trump was president, people were dying, the Earth was warming and growing more unequal, and it was hard to know what we could do about it.

It turned out to be the perfect moment to be inspired by the life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

At the end of March, the Zinn Education Project — coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change — began weekly seminars on the “History of the Black Freedom Struggle.” The idea was suggested by Brooklyn College professor Jeanne Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. The first two seminars were conversations on Rosa Parks between Theoharis and Rethinking Schools editor and Seattle teacher Jesse Hagopian.

Theoharis pointed out that although surveys have indicated that Mrs. Parks may be the most famous woman in 20th-century U.S. history, in the conventional curriculum and popular imagination, she remains “trapped on the bus.” She also remains trapped in the myth of the lone tired seamstress who changes the world. Her life was much more than the moment when she refused to give up her seat when ordered to move by a white bus driver in Montgomery, Alabama. Mrs. Parks’ life is a tapestry of resistance. And, indeed, she spent more than half her life in Detroit — which Mrs. Parks called “the Northern promised land that wasn’t” — fighting segregation in housing, hospitals, and restaurants; protesting police murders of Black teenagers; organizing against sexual violence; working for Congressman John Conyers and getting to know Malcolm X. Rosa Parks’ life offers a road map from the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter and #MeToo.

The conversations between Theoharis and Hagopian were wonderful, filled with story after story of Mrs. Parks’ lifelong commitment to racial justice. (Both sessions are archived at the Zinn Education Project.) Theoharis emphasized the key lesson she wanted us to draw from Mrs. Parks’ life: “You have to dissent even if you don’t know if it will matter or succeed, even if you can’t see where it will take you.”

This was a blast of hope in hard times — coming about two months before the anti-racist rebellion sparked by the murder of George Floyd. Theoharis’ prescient message was echoed by participant evaluations: “You don’t know when history is going to grab you and where the turning point will be. I’m not going to underestimate my ability to protest, not going to discount my actions and attempts to make a difference.” And “we never know which of our multiple acts of activism or resistance will be the springboard to change.”

Listening to Theoharis tell stories about Rosa Parks’ “rebellious life,” it struck me that one way to animate Mrs. Parks’ decades of activism would be for students to encounter some of these episodes through a mixer role play. In a typical mixer, like on the U.S. war with Mexico, students take on the personas of different individuals around one event, era, or issue. They encounter numerous, sometimes conflicting, perspectives through meeting and talking with one another. This new activity would flip that approach upside down: Every student would instead portray a different moment in the life of a single individual — Rosa Parks. And through conversation, students would surface the patterns of defiance on behalf of justice that coursed through her life.

Teaching the Mixer

I wrote the roles in the first person, from the perspective of Mrs. Parks, to make it easier for students to speak in the “I” voice when telling each other stories about her experiences. No doubt, it was Rosa Parks’ brave act on that Montgomery bus that helped spark the modern Civil Rights Movement, but I wanted students to meet Mrs. Parks at multiple points throughout her defiant life. For example, one role describes a 6-year-old Rosa in the midst of the 1919 Red Summer terror, with her grandpa — and his rifle — on the porch: “He had been born into slavery, and had been beaten and nearly starved as a boy. He was not going to allow the KKK to treat us like we were still in slavery. I stayed awake with him some nights, keeping vigil with him. I wanted to see him kill a Ku Kluxer. Sometimes we would sleep with our clothes on because we were afraid that we might be attacked in our sleep.”

And, of course, I wanted students to learn about Mrs. Parks’ eventful post-Montgomery life. By failing to acknowledge her long anti-racist work in the North, conventional treatments of Rosa Parks reinforce the notion that civil rights struggles were solely a Southern phenomenon: Bad South, Good North. Also, by shutting her biography before her long work in the North, Mrs. Parks stays confined to the traditional Civil Rights Movement, but cut off from her association with the Black Power movement.

In July of 1967, during the rebellion in Detroit, and in what turned into a “police riot,” as Rep. Conyers called it, police killed three Black teenagers in the Algiers Motel. The police claimed self-defense and were never charged. From the mixer role about this event: “Some young Black Power activists decided to hold a ‘People’s Tribunal’ to try to get the truth out. They asked me if I would serve on the jury. I said yes. It took place in Rev. Albert Cleage’s church. . . . The church was packed; journalists from Europe came to cover the event. It was very controversial and there were death threats. But we listened to all the evidence of what had actually happened that night — and found the officers guilty.” (The full lesson, with the roles, is posted at bit.ly/RosaParksMixer. Also, see “Organizing the NAACP Youth Council” on p. 33 for a sample role.)

I am aware that some teachers are uncomfortable asking their students to assume the personas of other people throughout history. When I do these activities with students, I emphasize that, of course, we can never know what another person is thinking or feeling, but studying history requires imagination, an attempt at empathy. When we use the “I” voice for another person in history, it is part of our effort to consider the world from that person’s standpoint. It is a gesture not of appropriation, but of respect and sometimes solidarity — albeit one that needs to be exercised with humility. And in the instance of imagining ourselves as Rosa Parks, it is an invitation to look at social reality from the point of view of someone whose entire life was dedicated to making the world more equal and more just. It’s a stance we hope our students will emulate. (See “How to — and How Not to — Teach Role Plays” at the Zinn Education Project at bit.ly/RulesForRolePlays.)

In writing the short scenes in the mixer, when possible, I used Rosa Parks’ own words. At times, the descriptions draw on the words of other people recounting their memories of what Mrs. Parks said. Some parts of the roles come word for word from the elegant prose of Theoharis. And, in fact, a few of these roles were written by Theoharis herself, who reviewed the full activity and graciously allowed the use of her book for this lesson. (A young people’s edition of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks will be published by Beacon in early 2021.)

I wrote the mixer with high school students in mind, although I have done it mostly with groups of teachers and teacher educators, via Zoom. Anyone who has tried to transfer a critical, participatory curriculum to online teaching knows that the simplest pedagogical move — “Turn to the person next to you and talk about your thoughts on . . .” — becomes immensely more difficult. I began the online classes by offering people some of the context above, before they received their roles. There are 22 episodes from Mrs. Parks’ life included in the mixer. Along with the roles are questions that participants can use to guide their conversations with one another — e.g., “Find a time before Mrs. Rosa Parks lived in Montgomery when she stood up for what she thought was right”; “Find a time when Mrs. Rosa Parks acted in solidarity to support another individual or group. Who was the individual or group, and what did Parks do?”

As I would if we were in class together, I asked people to read their role several times, and to list the three or so things that are most important and that they wanted to be sure to communicate when they met other people representing different episodes of Mrs. Parks’ life. I then went over the eight questions and asked participants to note those that they would be able to help others out with, based on information included in their role.

Face-to-face, a successful mixer is electric, with animated conversation filling the room, and participants darting from person to person as they complete their conversations. Students try to find a different individual to help answer each of the eight assigned questions. Obviously, Zoom makes this more challenging. Pandemic mixer teaching has been trial and error. It would be nice if Zoom allowed for a seamless mixing of paired students — so one pair could end a conversation and go directly into another pair, as students do in the classroom. Alas, Zoom hasn’t yet figured that one out. I began by clinging to the eight-conversation target of an in-person mixer, but this didn’t work: Paired conversation followed by a return to the big Zoom room followed by another paired conversation — repeated eight times — leads to Zoom fatigue. The sweet spot I’ve arrived at is three separate conversations of three people, in five-minute rounds. This allows for each participant to encounter six roles or episodes, in three brief conversations.

When we do in-classroom mixers, there are some cautions that I share with students. One is to emphasize that these are real people’s lives, and we want to approach them with respect, not caricature. We are trying to faithfully represent their ideas and experiences, but this is not a play; in this mixer, we are not trying to “perform” as if we are Mrs. Parks. Students should not attempt accents or behavior that they think might be like Mrs. Parks. However, as mentioned, I do ask people to use the “I” voice, to attempt to enter the persona of Mrs. Parks and share her experiences with one another in the first person.

Before I did this activity, I was concerned that this would feel strange or silly, with everyone speaking as Rosa Parks. Rather than feeling awkward, “Each conversation built a more fully developed human and challenged the singular story of Rosa on the bus,” as Washington, D.C., English professor Jill Weiler noted in the Zoom chat. Esther Honda, a San Francisco teacher-librarian, added, “Love meeting all these Rosa Parks.” In the most recent workshop I led, I represented Rosa Parks when she was 6 years old and met other students-as-Mrs. Parks doing activist work in Detroit and during the Montgomery bus boycott. That was my experience, too: I loved meeting all these Rosa Parks, at different points in her life.

As I do when I lead an in-person mixer with students, after people met one another in small groups, I asked them to pause for a few minutes to write about their experience:

• What aha’s came up for you in your conversations?

• What delighted, surprised, or intrigued you about events in Mrs. Parks’ life?

• How does Rosa Parks’ life connect with what’s going on today?

In our Zoom sessions, I did not listen in on small groups’ post-mixer conversations, but people shared thoughts in the chat and in their workshop evaluations. Brianne Pitts, a teacher educator from Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, wrote: “I loved how much childhood activism came up. I think these stories and experiences of Mrs. Parks showcase how much students’ current realities matter, and that they can relate to some of Mrs. Parks’ early examples of standing up for herself — seeing that it was all connected. Her activism was a lifelong project.” Some participants focused on specific incidents that they found significant. Washington, D.C. teacher Jessica Rucker wrote: “The details that most stand out are that their marriage [between Raymond and Rosa Parks] happened right in the middle of the campaign to save the Scottsboro Boys (when she was about 19 years old) and that she and Mr. Parks owned guns and were willing to use them to protect and defend themselves against white vigilantes.”

The one high school student in our Zinn Education Project workshop, Nia Bethel-Brescia, from Norwalk, Connecticut, wrote, “I loved learning about different kinds of youth activism that were included in the activity. I think that’s so important in education, to showcase the role and impact of young people, because that’s who you’re teaching to! It was cool to see the ways that Mrs. Rosa Parks stood up for herself and fought for herself as a young person. Additionally, to that point, I like how the lesson makes it clear that fighting for justice is a lifelong struggle, not just something that happens under a movement or for a couple years at a time.”

Although the conventional curriculum may trap Mrs. Parks on the bus, the fuller story of the Montgomery bus boycott is one of the most inspiring in U.S. history. It’s one included in the mixer activity, about the immediate aftermath of Rosa Parks’ arrest. She was arrested on Dec. 1, 1955, a Thursday, and, of course, she had not intended to be arrested — in fact, she was distressed because she had NAACP work to do on the weekend, and this was a disruption. On Friday evening, there was a meeting with community leaders and ministers at the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to talk about what to do. Before Mrs. Parks arrived, she wondered to herself “whether my getting arrested was going to set well or ill with the community — the leaders of the Black community.” Yes, she actually thought that people might be unhappy with her for taking this stand. And when community leaders decided on a one-day boycott starting Monday morning, to coincide with Parks’ appearance in court, no one was certain that Black people in Montgomery would heed the call.

They did. The boycott lasted 381 days.

But on the Wednesday before the Thursday that Mrs. Parks refused to comply with the bus driver’s order to give up her seat, it would have been inconceivable to think that something was about to happen in Montgomery that would change U.S. history. As Howard Zinn wrote in his autobiography: “Everything in history once it has happened looks as if it had to happen exactly that way. We can’t imagine any other. But I am convinced of the uncertainty of history, of the possibility of surprise, of the importance of human action in changing what looks unchangeable.”

And that is a key lesson that can be drawn from Mrs. Parks’ life. Hers was a life of conscience and activism and principle — but with no guarantees that any one act would have transformative consequences. Rosa Parks’ story — the real version — teaches us that we work for justice without being sure that it will make a difference. And in a society like ours, riddled with racism and vast inequalities of wealth and power, this should be a source of hope because in a short period of time, things can change profoundly.

SAMPLE ROLE

Organizing the NAACP Youth Council

In the early 1950s, in Montgomery, Alabama, the main library did not allow Black people to check out books. I helped organize the NAACP Youth Council to stage protests at the main library. Again and again, we would show up and request to be served. But the library refused to change. Just because we protested didn’t mean we were going to win. But I was so encouraged by the action-oriented nature of the young people I worked with. One of things I liked about the youth is they started right in to write letters to Washington about anti-lynching legislation. They didn’t spend a lot of time arguing over motions, and there was a difference from the senior branch of the NAACP in their way of conducting their meetings. Many young people were warned by their parents and teachers not to get involved in civil rights. There was this popular phrase: “In order to stay out of trouble you have to stay in your place.” But when you stayed in your place, you were still insulted and mistreated if white people saw fit to do so.