Teaching the real stuff of the world: bears and learning together

Elaine MacIntosh is a retired elementary teacher who worked downtown and in Scarborough, with primary school kids. In 1989 she developed a science program on bears with her Grade 2-3 class situated in a working class neighbourhood in Scarborough. Elaine’s approach to teaching, in general was to find ideas and language that suited the students from the neighbourhoods in which she worked. There was plenty of structure in her teaching, but what made it special was the whole language approach she took.

This was not uncommon back in 1989. The central idea of whole language is in its name. Use language in as many ways as possible; make it something children can use to express their strongest thoughts, feeling and perspectives on the world as they see it. Make it truly useful learning.

This is in sharp contrast to current practices of teaching to make sure that students do well on the grade 3 and 6 Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) tests. But Elaine along with other teachers like her was able get her young children to move ahead quickly in reading and writing simply because she encouraged them to take their scholarly enquiries seriously.

What follows is an interview she did with her partner, George Martell for Our School Our Selves back in 1989. She developed, with her students, a unit about bears. But it was so much more than that. She treated her students as serious investigators, providing them with plenty of reading material and support. She expected them to support and provide useful advice to one another. She also expected them to take their studies as seriously as she did; they reworked and rewrote sections of their projects until they were ready to publish.

She also took the time she needed to integrate science, reading and writing in a truly useful and meaningful way.

Her description of the work is as relevant today than it was in 1989.

George Martell (GM):

As I looked around your classroom during this work on bears, there must have been at least fifty or sixty books and articles on the subject available for student research. That’s a lot of information for these little kids to take in. What do you day to people who think you’re asking too much of our students and overwhelming them with too much information?

Elaine MacIntosh (EM):

It’s a long answer, I’m afraid. The first thing I’d say is that this kind of science program isn’t simply laid on by me. I suggested earlier in the year that animals might be a topic for study. In this I always get 100 percent support; kids of this age love investigating animals. Around November I talked with them about a number of animals they might look at and left a wide variety of materials on different animals on shelves and tables, which they could leaf through at any time during the day. I also suggested they go to the zoo and think of the animal they’d like to study. The Chinese pandas were there at the time and they made a big impression. After a month or so it became pretty clear that bears were on the agenda, and in January, when we took a vote, bears won hands down. So, from the beginning there was a sense among the kids that they had some ownership of the project.

We then began a process that had very little laying on of information -thought it had some of that. What was learned was much more by way of. Collective research and discussion – a process in which the kids and I and the kids among themselves got hold of this subject together. We were honestly curious about it (I certainly didn’t know much about the various bears when I started) In this, I think, there was some real science going on; not the awful stuff that high school students have to suffer- filling in physics formulas by rote or getting the ‘right answer’ in chemistry lab. My grade 2s and 3s really thought about this subject- how bears lived and what their physical beings were like.

GM: How about telling us a little about the research first.

EM:

As you mentioned I had all these books and articles around. I got many of them from the library – it was very well stocked – and some from my own collection. I read to them the most interesting material I knew about bears – from novels and science books. And I laid out the rest of the books on the science table, along the blackboard, on various shelves and display counters and let the kids browse.

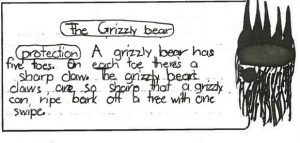

In this context you don’t have to worry about overloading them with information. They take what they – what really captures their imagination. They’d be drawn, for example, to pictures of little bear babies and descriptions of how they were born… Or they’d be scared to death by the ferociousness of the grizzly. They were really interested in the grizzly bears’ claws.

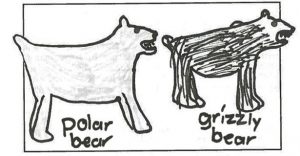

As we browsed, we got into discussions with each other. Which was the meanest or scariest bear? What were the different kinds of foods that bears ate? How did they protect themselves? We compared cubs of different animals; whether they stayed for one year or two. Whether there were one or more babies. How did the parents protect their cubs? What were the differences between the panda, the polar bear and the Alaska brown bear?

As we browsed, we got into discussions with each other. Which was the meanest or scariest bear? What were the different kinds of foods that bears ate? How did they protect themselves? We compared cubs of different animals; whether they stayed for one year or two. Whether there were one or more babies. How did the parents protect their cubs? What were the differences between the panda, the polar bear and the Alaska brown bear?

We looked at different footprints for different kinds of bears. We thought about different sizes and weights. We measured how far up the classroom wall a grizzly bear would stand – way above the blackboard as it turned out, which we thought as really tall.

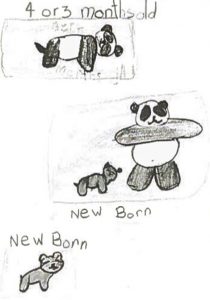

Jennifer found out that pandas weighed 4 ounces at birth and we approximated this on balance scales. We learned that panda eyes don’t open until they’re 40 days old and that they can’t crawl before they are 3 or 4 months old. So, we could compare them with kittens, which most of us knew about. So many kids, even if they had never seen a bear had thought about bears or dreamed of them and were now grateful to see them for what they really were. Scary alright, but not so frightening as they were when they were unknown dark creatures in the woods.

Jennifer found out that pandas weighed 4 ounces at birth and we approximated this on balance scales. We learned that panda eyes don’t open until they’re 40 days old and that they can’t crawl before they are 3 or 4 months old. So, we could compare them with kittens, which most of us knew about. So many kids, even if they had never seen a bear had thought about bears or dreamed of them and were now grateful to see them for what they really were. Scary alright, but not so frightening as they were when they were unknown dark creatures in the woods.

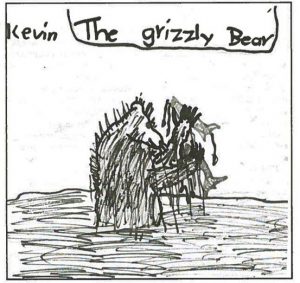

They were gripped by the details of the bears’ lives. They wanted to get them right We’d all been told that bears hibernate during the winter. They don’t really hibernate; they just sleep. A true hibernation occurs when an animal’s temperature goes much further down. They especially wanted to get the physical qualities right.

Here’s Kevin’s picture where he tries to show the hump on the grizzly bear’s shoulder is unique to it and that it isn’t the same with the polar bear.

GM:

I think, to some people, of student choosing might sound like a liberal smorgasboard approach to science rather than something solid and systematic. What do you say to that?

EM:

My answer is that I think this is real science. The kids are acting like scientists trying to figure out what the real world – in this case the worlds of bears – is all about. If there is a technique here it’s the process that puts kids into the centre of this real thing, opens them to a lot of solid information about bears and then lets them sift through it to recover and eventually write about. The real world is exciting and kids want to respond to it seriously.

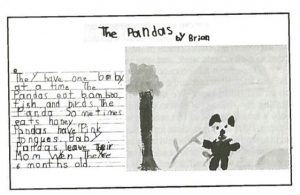

Let me tell you about Brian.

Brian was the youngest kid in the class – working at a grade 1 level in Grade 2-3. His previous teacher thought it best to keep him back for another year, but his grandmother, a very caring and hardworking person who was raising him, didn’t want it. She’d had bad experiences with Special Education with her own son and didn’t want Brian to go through anything like that. She was especially concerned that he not lose the friends he had been going to school with.

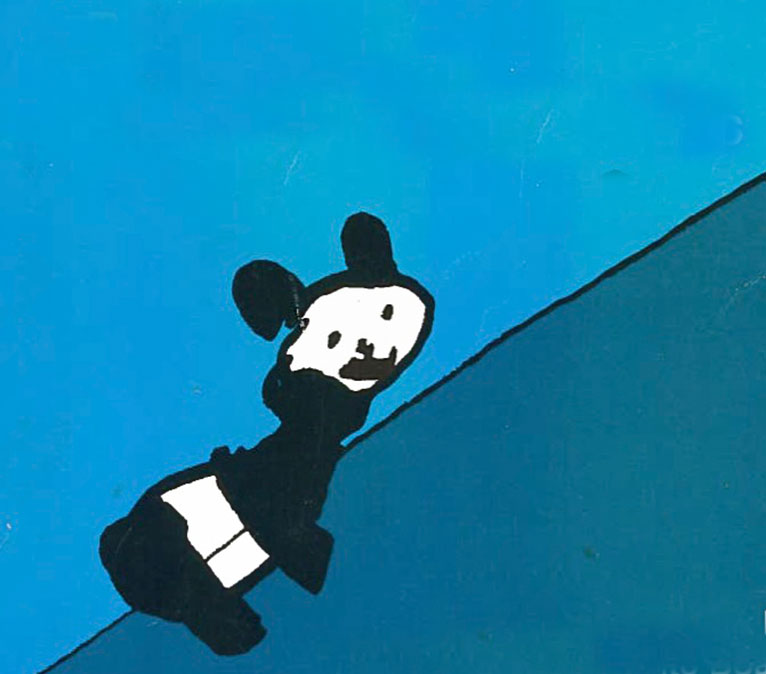

I was worried about Brian being able to connect with the project. But it turned out he was really interested in pandas. Like many other kids he was especial interested in the fact that pandas play. He was delighted that pandas like to slide down hills and are willing to walk up a hill just to slide down it. Just wanting to play.

I was worried about Brian being able to connect with the project. But it turned out he was really interested in pandas. Like many other kids he was especial interested in the fact that pandas play. He was delighted that pandas like to slide down hills and are willing to walk up a hill just to slide down it. Just wanting to play.

Brian was also a very feisty little kid. If everyone else as going to produce a book on bears, he was determined he would too. He went through some very discouraging times and sometimes got turned off and didn’t work as hard as others.

Nobody just sat down and wrote one of these books, you know. They spent hours and hours writing out the information… and then they would set about organizing it in conferences with other kids and me. After they wrote it out in final draft, they had to write it out again for publishing.

In all of this, I was afraid that Brian would get really discouraged and give up. But he was terrific about it. He had to re-write many times… but he ground away… It was really tough for him to eke out information from the material in class. He’d go to the books I’d read – sometimes books I’d read more than once- and pour over pictures and maybe get a line or two. I’d read to him directly sometimes and so would some of the other kids. He never really stopped hanging in and, in the end was very excited about his production. Later he would often go to reread his book. At the time, his reading was quite limited and it gave him a big boost.

GM:

You’ve touched on some of the “discussion” part of this “scientific” process and I was wondering of you could tell us a bit more about it in detail.

EM:

Perhaps I should say first that the reading and the discussion and the writing all go on at the same time, which is how it is in real life. There’s no neat sequence. Of course, you have to have some initial discussion and research before the kids can get down to any writing, but after that it goes back and forth in many different ways. Let me try to get at it from a couple of different directions.

There was a pretty wide spread in the different kinds of bears the kids decided to write about- pandas brown bears, grizzlies, polar bears etc. When one of them hit a book that was really tough or had a difficult problem thinking through or writing about it, I would have a discussion with them or read from one of the books for them. But often I wouldn’t focus on just one kid. I’d gather around everyone for the reading or discussion even though for many it wouldn’t be about a bear they were doing. But they didn’t mind at all. In fact, they’d often take off with this new conversation themselves in different corners of the room. They were interested in each other’s work and very interested in discussing it.

Throughout this process I never imagined that I should give the kids a research task and then let them get on with it themselves. We must have spent a month and a half reading about bears (of course we did other subjects as well) and only a small amount of this reading was done before they started writing. I’d make suggestions for books, read from books they might want to read and the kids would make suggestions for each other.

All the time, individual kids kept adding to the information they had in conversation with us all. I read to the whole class on bears almost every day. By the end I was reading pretty difficult material and encouraging them to do the same. We also saw films in which they could see bears in the wild. One film was fantastic in showing how a polar bear would float flat down on a piece of ice to get close to a seal. The kids were really impressed that an animal could think so cunningly.

Throughout this period, the kids were teaching each other and not always about the bear they were working on in common. In conferences one kid would begin to talk about the food his or her bear ate and then another kid would say: “Yeah, but you should see what my bear eats.” They were all excited, for example, about the work “omnivorous” which one boy came up with when finding out that his bear ate both plants and other animals and fish. It was great fun to have this long word they really knew the meaning of.

They were fascinated by the panda’s thumb not really being a thumb, but rather a wrist bone. We all felt our wrist bones and thought about them growing out and becoming thumbs. In her book, Jennifer (Grade 2) made sure to call it a “radial sesamoid bone.”

GM:

Where do the kids go from here? What develops from this plunging into nature – the world of bears in this instance? What kind of thinking?

EM:

Well, they do learn about categories and not in a boring, mechanical top-down way. The categories come out of the material they are dealing with and help structure it for them.

We had discussions about organizing the material they were writing. I started by suggesting section titles so they’d have some handles on the material and somewhere to put it. We talked about what they would like to know about and categories like “appearance” would emerge or “babies/”cubs”/”family” which they could use to cover material about children or infants and their parents.

“Interesting facts” emerged as a category for what got stuck in their heads when it was all over, something that was outstanding, but didn’t fit anywhere else – like grizzlies having a wide range of colours from creamy white to black – which Kevin learned.

They also learned to think more generally about the subject they were studying. Environmental issues came to the fore pretty quickly. They talked over and over again how the panda was endangered and what should be done about it. They had good hard facts to build on. They also got into hunting- how humans are so careless and thoughtless and selfish. They thought about the seal hunt and fur coats, how it seemed cruel and unnecessary and how the native people and fishermen needed it.

The thing that made me most excited was that after we had done all this research and writing about bears, they wanted to go off and do other animals. To be scientists on their own. But, I should add, always in the context of having their buddies around to discuss their explorations and newly acquired information.

GM:

How did that happen?

EM:

It seemed so natural.

Look, for example, at this section of Jennifer’s book, where she is linking the giant and red panda with the raccoon family. You can see her delight in these different animals and with her knowledge of them. Kids like Jennifer just want to go on with it. It’s frustrating for them.

After completing their books on bears a number of grade 3 kids were so excited about being able to do this work that they insisted I go and get them a bunch of books from the library. So I got them a whole bucket of books on birds or lions or whatever. Here is an example in Adam and Robin’s research, The Praying Mantis.

Maybe I should tell you about Derick’s lion book. Derick joined the class a year before, in the middle of grade 2. He seemed very soft and sweet but really had some very strong leadership qualities about him. At the time, he was struggling with a lot of difficult changes in his life, but his new dad seemed a very caring person and his mom was solidly on his side and very loving.

When he came to the class, he had no confidence in his reading ability and was, in fact, a very poor reader. But he worked very hard and, by Grade 3, was a good confident student. He’d also become a classroom leader and carried a lot of respect. I could say to kids doing badly in Grade 2: “Look at Derick; he had more difficulties with his reading than you and look what he’s done. You can do it too.” And they knew I wasn’t talking about a sucky kid. He was respected. Because the work was collective and serious, doing it well didn’t make you a teacher’s pet.

Anyway, Derick decided he wanted to do a lion. He came up with his own headings and changed them as he went along. He read as much as he could. I didn’t help him at all in this. Of course, he consulted his buddies, who talked about it with him, just as he talked about their work. They would hash everything over. They even decided how many days they wanted to work on their projects; how much information they wanted. But each did his own work. And Derick worked long and hard in the time he and his friends set for themselves.

GM:

What are the standards operating here? How do you know your kids are doing good work? How do you tell others that?

EM:

My standards are based on my internal understanding of each child. I expect their individual best.

GM:

You don’t mean they’re just subjective? You think other people will agree with you don’t you. You think Brian’s panda sliding downhill is just great, for example, and you expect me to say the same.

EM:

Sure, but I also know that standards are sliding things. You can’t forget where the kids are starting from. A drawing from one kid may be exceptional, while the same level of skill may be just so-so from someone else. The first kid may have really sweated over it, and the second didn’t really need to try that hard. I’ll be critical of the second and try for a harder standard.

GM:

But you have a direction for your pushing, an idea where the kid should end up an idea where most of the kids should end up.

EM:

I do, but I’d be hard-pressed to find the right words for it. One way into it is to is to understand how the collective of all the kids helps make your standards. When, for example, Brian finishes something that’s good, everyone rushes over to look. They tell him it’s great and they are inspired to do better themselves.

Standards are collective in that way. We had, for example Lance, a native kid in class. He was way behind in school, but he was cool and gained an increasing amount of respect as the year went on. Discussions with Lance got us started talking about racism in the world, how native people had been put down, and how American movie makers had made them look like such nasties. There was a lot of straight talk. Lance had a strong character and became something of a hero to the other kids. At the same time, they all knew that writing was a struggle for him.

There was no pretence about this. Most everything about each child, after a while, was accepted as an ok truth. There was an accepted understanding of how things are. So, Lance wasn’t humiliated by his writing problem, and he didn’t have to hide it. Gradually, he started to do much better work and that too was understood by everyone. Some days I’d have to get after him: “You do fabulous work,” I’d say, “and them all of a sudden you’re sitting around on your thumbs. What is this? You can do much better than this.” Lance didn’t think I was unjust and neither did anyone else. The same thing happened to other kids.

We all knew what was true and built our standards together. And we moved together to a more solid grasp of the material, more insight, better expression. What else is there?

GM:

Do the parents believe you? How do you convince them this isn’t mindless liberalism? How do you show them that their kids are coming away with something solid?

EM:

I think it’s right there in the production. The writing is there; the books are there. And so is their ability to read. The kids can sit down and read books to their parents.

And, in case you’re wondering, they do alright on mechanical reading tests like the Gates McGinitie, which I don’t think test very much. There is a lot of phoniness in these tests; they’re tricky in ways kids don’t expect. Kids aren’t looking out for tests to be tricking them; they expect tests to be finding out what they know.

But relative to other classes, this class did fine on the Gates and some kids actually jumped ahead quite a lot. I should add that if you want your kids to do well on mechanical tests, you have to teach them – especially about the tricks. In the “reading comprehension” sections for example, they have to be taught to pay attention to banal stories and answer mindless questions about them. So, doing well on the Gates doesn’t mean much to me.

What I know about these kids is that they have a much stronger base of literacy than what is reflected on the Gates; it’s something they can really move forward on. It’s linked to their human desire to really know about the world.