Thank you George…

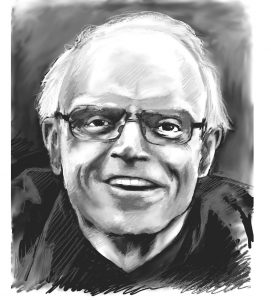

We’ve lost a true brother. George Martell, deeply loving husband, father and grandfather, friend to more people than he could count, mentor to even more, passionate educator and tough political activist has died. It comes after living with leukemia for two years during which time he continued to do everything he could to hang on – to his family, his friends and the fight to make education mean something in this province.

To Elaine and his family – know how much George meant to all of us.

George thought he had only a few weeks to live – that was two years ago. But what he calls a “Hail Mary Pass” from his oncologist at St. Mike’s Hospital saved him for while at least. He thought she was great, liked the way she didn’t mince words, telling him what was happening with his leukemia, making no bones about the fact that a new drug was no sure thing and that he might have a couple of months or maybe a bit longer. Typical of George, he couldn’t help but ask her what drove her- how she coped with all the death and disappointment that surrounded her and her work and still kept going. She said simply: “I’m a Catholic –it’s faith.”

This may not seem to be the most obvious way to open up a story about George, but he loved that answer – not the Catholic part, but “faith” in something bigger than yourself and hard to grasp. He worked most of his life with possibilities, like schools that could become the hubs of their neighbourhoods and truly reflect their needs; schools centred on teaching children rather than on the narrow prescriptions of curricula. These things were so brutally hard to achieve, sometimes so far down the road, how could you ever push forward without some faith and a firm belief that something larger and significant could happen?

This view of the larger picture meant that George was not bound by the status quo – even if that meant disagreeing with his progressive allies. Last summer for instance, we were just starting School Magazine and going over an article on Doug Ford about cancelling the Liberals’ sexual education curriculum. Everyone who wasn’t a strict social conservative was furious about it- all set to rail at Ford, sue him and demand the return of the curriculum. George said the Liberals’ curriculum, while much better than Ford’s, was still awful; it was dead. That was not what we were expecting to hear.

What did he mean?

Well, he explained, there’s all this dry information, details even law, but there’s no humanity; it doesn’t say anything about love about romance. And he was right, for a curriculum about something as complex and intangible as human relationships, it pretty much crumbled up on the page. It was the epitome of what he’d been arguing about since the sixties; it didn’t come from schools, neighbourhoods, families or kids. As far as he could see it might as well have been written by a bureaucrat in a cardboard box.

But then, George was driven by the connection between personal and political life. It was the idea that you could never just stand above the world and dictate to it in some cool detached way – like writing a curriculum that really just ticked the right boxes. You had to start with people, including yourself and work from there. You had to work in neighbourhoods, talk to people and find out what their schools really needed to make them serve their kids. And that wasn’t about achieving high scores on meaningless provincial tests or developing regulations for parent councils. It was about applying what you knew and could learn from others to your local school. It’s the idea stamped on one of the magazines he started: “Our Schools/Our Selves.”

What George understood early on, was that education and educators needed to have this connection too. When he was a trustee for the old Toronto Board of Education, he was pushing for an overhaul of special education because it left so many immigrant and working class young people in the bottom stream of schools where they had little hope for a decent future. He developed and wrote some of the “Where We Live” series of readers back in the seventies because he realized that the same boys and girls didn’t have anything to read that reflected their experiences. More recently, he had been pushing for the idea of a much stronger bond between Indigenous, immigrant and working class people, something he saw as absolutely necessary if there was ever going to be true democracy in education.

It was never just one issue. Recently when he saw that there was a 50 percent dropout rate among inner city students and in particular the Somalian community, he dragooned his York University students to work with the school, students and their parents.

He’d likely scoff at this – “dragooned never!” – just an exercise in comradely persuasion. One of his friends, Hugh Mackenzie spoke to him over a live feed we’d set up a couple of years ago for a party in honour of George that he was too ill to attend. Hugh began by saying “I’ll choose my words carefully because there’s always the risk that something you say might be taken as volunteering to do something.” You knew you were in trouble he added, when George would say something like “you wouldn’t believe what they’re doing” and the conversation didn’t end until you’d volunteered to do something to help. Sometimes you didn’t even know what hit you. You’d find yourself helping out with a campaign to stop closing a school or something and wonder how you got there.

He’d fix his blue eyes on someone whom he figured could help in a worthwhile project, and with such gentle solicitude say something like: “You know…this situation is, well, it’s very bad and it would be just so good if you could …. You don’t suppose you could spare a bit of time to …” George called this “looking into your soul.” And it worked. He had that – it must have been innate – talent to get people to do what they would eventually find out they really wanted to do, but just didn’t know it.

So many people thanked him for that – for saving them from the teachers colleges of the seventies, for helping them get started writing or in politics, for showing them how to organize their neighbourhoods, for setting up a framework for some kind of action, then amending it, then adding to it, then amending the addition so that by the time they’d finished reading it, they were involved. They thanked him for his relentless optimism, that he “got” class in education, that he advanced large ideas about it, but always began with the local school.

George faced his own death in a way that illustrates everything written above. He had an idea of what he wanted to do even if he didn’t know how long he had to do it. He wanted to spend time with his family and was quite clear on limits he set for his time with visitors. But George still gave a lot of time to others, getting School Magazine started, letting us use the credibility of his name to get emails returned. He even gave a lengthy interview just a few days before he went into the hospital for the last time. He told educators to get serious – to believe that they know what schools need and to fight for it.

In the end, it’s best to give George the last word – some of his thoughts to everyone gathered at the party he had to watch on TV:

“Dear Friends,

Let me say first, how grateful I am that this gathering is taking place. The people in this room mean the world to me. As you can imagine, I do so wish I could be with you tonight. Elaine and I are glued to our television set and taking you all in on You Tube.

You know when your time is short, the importance of love in your life hits you like a ton of bricks. I have been so blessed in my life; a loving marriage, wonderful kids and grandchildren and so many friends.

Many of you here tonight are so precious to me. What strikes me now is that what we share is how important love is in our lives and I think that’s what brings us together in the most fundamental way and I don’t mean that sentimentally.

I would say that it applies to ourselves as teachers, about our relations with our students. What we know is that loving our students is what we do as teachers. What that means in opposition to the vicious corporate agenda in our schools is that every one of our students has their own extraordinary human spirit. It will be with them all of their lives, and it is our job to help our students realize that spirit…”

_________________