What did you learn in school today? Music education and the teaching of history

This article appeared in the October 2016 edition of Our Schools Our Selves, published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

What did you learn in school today Dear little child of mine?

What did you learn in school today Dear little child of mine?

I learned that Washington never told a lie. I learned that soldiers seldom die.

I learned that everybody’s free,

And that’s what the teacher said to me. That’s what I learned in school today, That’s what I learned in school.

~ Tom Paxton

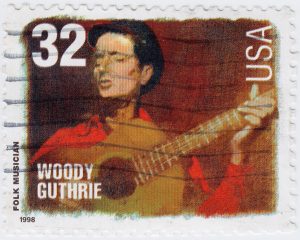

In the Fall of 1987, I walked into New york City Public Intermediate School I.S. 44 with a guitar on my back. I had no qualifications whatsoever to teach music, but I wanted to volunteer in the school with the hope of eventually securing a full-time teaching position, and music was my entrée. Drawing on my amateur experiences songwriting, performing, and co-founding a university student group called Folksinging Together, I volunteered to

teach folk songs to some of the middle schoolers at I.S. 44. We sang Guthrie, Dylan, Ochs, and (Joni) Mitchell. The songs of Peter, Paul and Mary, Tom Paxton, Malvina Reynolds, and Pete Seeger were regular fixtures. David Mallett’s “Garden Song” became a de facto (if somewhat parodic) school anthem. After a few weeks, I benefitted from happenstance: when a teacher abruptly left for a district administrative position, I was offered a job as a full-time teacher.

Although I was not a music teacher, music remained a part of my engagement with the school both within the core subject area classes I taught (including social studies) and through my continued informal folk singing with the children. For example, after sharing the Tom Paxton song (shown above) with some of my classes, my students and I discussed the relationship between “facts” and “interpretation,” gaining a foothold on more complex issues of epistemology and authority. We compared excerpts from textbooks and newspaper articles from different countries around the world that described the same historical events. We asked about the interests embedded in particular narratives and the choice of particular facts and interpretations. We turned a critical lens on the very folksongs we had learned earlier. “What did you learn in school today?” became a popular refrain, recited whenever we were collectively calling into question any presupposed truth.

I recall this now, as I think about the (potential) relationship between music education, history teaching, and democratic engagement.¹ My research in social justice education and the role of schools in democratic societies leads me to recognize music as one of a number of powerful mediums through which educators interested in the democratic purposes of schooling might pursue their goals. I agree with Stephanie Horsely (2015) who argues that “musical values can foster the types of social democratic behaviors desirable for broader public participation and engagement.” A former doctoral student, Joan Harrison, and Professor Paul Woodford among others have taught me that those values can be nurtured within the music teacher’s classroom, but here I am more interested in the use of musical approaches to teaching in any classroom (including, of course, the history teacher’s classroom).

I see at least three ways that music is salient for history teachers and how music teachers and history teachers might partner in their efforts to teach a robust critical sense of history. First, music contributes to the overall diversity of pedagogical approaches available. Second, music offers a powerful way to connect a variety of academic lessons to the real-world passions that bring those lessons to life. And third, music and those real-world connections and passions it engenders, frequently — although not always — spark broader social, political, and moral questions that might otherwise remain dormant. It is this third characteristic of music in history education with which this essay is primarily concerned.

Before I turn to the use of music in history education, I want to explore two obstacles to robust history education that music may in some circumstances be employed to overcome.

The demonization of social justice

The history of public education reform is replete with efforts to reduce the gap between the haves and the have-nots in society. Public education has regularly been enlisted as a means to ameliorate poverty, provide broader employment opportunities to underserved populations, ensure that students care about those with needs and treat all individuals with respect, and create policies so that — in more contemporary parlance — no child is left behind. These efforts, like all educational and social policies, work with varying levels of effectiveness, but few doubt the value of these goals. Indeed, public schooling itself could be considered one of the greatest experiments in social justice, based on the idea that all children, regardless of their socioeconomic background, are entitled to quality education.

At the same time that there is considerable unity around these goals, the term ‘social justice’ has frequently drawn criticism. In one of the more well-known battles around the pursuit of social justice in education, the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) was forced to drop all language related to social justice from its accrediting standards (Wasley, 2006). The Council was responding to pressure from officials in the U.S. Department of Education. Conservative groups, such as the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, the National Association of Scholars, and the newly-formed Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, led the charge. NCATE’s guidelines had simply required that teacher candidates in education programs “develop and demonstrate knowledge, skills, and dispositions resulting in learning for all P-12 students’’ (2001, p. 25). Then, in an appended glossary of terms, they suggested that these dispositions might include “beliefs and attitudes related to values such as caring, fairness, honesty, responsibility, and social justice’’ (p. 30). NCATE never said teachers must be committed to social justice. And they certainly did not say that a commitment to social justice was associated with particular political perspectives. But the appended reference to social justice as a goal was enough to provoke threat of censure until the reference was removed.

Conservative pundits have also waged a withering attack on social justice in education. Manhattan Institute Senior Fellow, Sol Stern for example writing for Front Page Magazine charged that schools are “openly infusing the themes of “social justice” throughout the curriculum (Stern, 2006). To make his case, he cites various teacher education and high school courses that mention ‘social justice’ or mention words that Stern identifies as smacking of social justice; for Stern and likeminded critics, any mention of “diversity’’ is a call to arms, as is the concept of “peace.” In short, the idea that teachers and students might tie knowledge to social ends is anathema to any conception of a good educational program. This presents particular obstacles to teachers of history and social studies who tie their work to strengthening principles of human rights and social justice.

Standardization as the enemy of critical thought

Almost every school mission statement these days boasts broad goals related to critical thinking — essential for robust history and social studies education. yet beneath the rhetoric, increasingly narrow curriculum goals, accountability measures, standardized testing and an obsession with sameness have reduced too many classroom lessons to the cold, stark pursuit of information and skills without context and without social meaning — what the late education philosopher Maxine Greene called mean and repellent facts.² It is not that facts — historical facts in history, mathematical facts and formulas in math, scientific facts in science — are bad or that they should be ignored. But democratic societies require more than citizens who are fact-full. They require citizens who can think and act in ethically thoughtful ways. Schools need the kinds of classroom practices that teach students to recognize ambiguity and conflict in “factual” content and to see human conditions and aspirations as complex and contested. These skills and dispositions are, of course, central to any robust lesson in history.

Increasingly narrow curriculum goals, accountability measures and an obsession with sameness have reduced too many classroom lessons to the cold, stark pursuit of information and skills without context and without social meaning.

As many scholars and pundits have made clear, however, both history and arts education have been subject to the repercussions of a broader shift in education reform that wants to see teaching and learning as a technocratic means to increasingly myopic education reform goals. At the same time that conservative attacks on social justice and critical thinking have hindered reforms aimed at tying the school curriculum to social ends, a recurring educational preoccupation with standardization has further marginalized efforts to make historical imagination central to students’ school experiences

Music educators are used to their classes being electives, called “non-academic,” and sidelined to make room for the “real” school subject areas. More recently, history education — like the arts and physical education — has also become elective, coopted in the exclusive service of developing writing skills, or removed from the curriculum altogether to make way for test preparation in math and language arts. At other times, it has been reduced to the same kind of formulaic fact-minding that plagues reforms in other subject areas. History teaching however, may be the target of neoliberal reforms for an even more pernicious reason. The past may be threatening if, instead of being presented with detached dispassion as something that’s done and over with, it engages students’ imagination, asking them to envision a society different from the one that is. The study of history, when done right, has the potential to awaken in students the realization that they are not passive spectators but rather actors in the long arc of change. And music can be a powerful pedagogical tool in that revelation.

History education, music education and democratic goals

Set against this broader context — attacks on notions of social justice and critical thinking in education reform and a cultural obsession with standardized tests in only two subject areas — it seems inevitable that history educators interested in more robust approaches to teaching history face an uphill road. What if history teachers prepare students to use the knowledge and skills they develop in the history classroom to identify ways in which society and societal institutions can treat people more fairly and more humanely? Nothing awakens the fears of mainstream education reformers more than the idea that schools might be enlisted in a critical analysis of contemporary social institutions and how they can be improved. But if standardization is the enemy of critical thinking and freedom of expression, the reverse is also true: critical thinking, creativity, and imagination are the enemies of standardization. Music is one example of such a worth adversary against uniformity and conformity. using music in teaching reminds us that education is a richly human enterprise and that understanding comes not from disconnected and disembodied facts but from the ways those facts are embedded in culture and politics and diversity of forms of human expression.

Indeed, education goals, particularly in democratic societies, have always been about more than narrow measures of success, and the use of the arts in teaching should be central to these concerns. Music may hold a special spot in the pursuit of those broader democratic goals. Saul Alinsky (1965) called dissonance the “music of democracy” and although his use was metaphorical, the connections between music and democracy, I believe, can also be literal. Teachers are called on and appreciated for instilling in their students a sense of purpose, meaning, community, compassion, integrity, imagination, and commitment, all features of a robust curriculum that uses music and art to engage the passions in the pursuit of a more just society.³

Moreover, subjects such as music and, increasingly, history which do not tend to be measured by standardized assessments, while marginalized in some ways, ironically, also constitute the places where teachers are more able to work under the radar of the education reform juggernaut. Although some school boards and districts ensure that demands for coverage of material prevent in-depth critical analysis, others — through benign neglect — have afforded teachers the freedom to study social movements, the role of youth in social change, competing conceptions of economic inequality, historical interpretation and so on. And some of those teachers have drawn on their own knowledge of music or teamed with music teachers to utilize the power of music to make these lessons come alive.

For example, a teacher whose classroom I visited was teaching the Civil War. As part of his curriculum unit, he invited the music teacher to teach the traditional African American spiritual “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” Together, they explained that the lyrics to the song provided hidden instructions to slaves pursuing freedom along the route of the underground railroad. “For the old man is a-waiting for to carry you to freedom,” the song instructs, “If you follow the Drinking Gourd.”

The riverbank she makes a mighty good road / The dead trees will show you the way

Left foot, peg foot, travelling on / Follow the Drinking Gourd

The river ends between two hills / Follow the Drinking Gourd

There’s another river on the other side / Follow the Drinking Gourd

What did the Underground Railroad accomplish in the context of slavery? What does it represent for other struggles for social justice? Was music dangerous then? Threatening? Is it now?

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the 2005 category-five hurricane that slammed the Gulf Coast of the United States, Kanye West’s criticism that “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” resulted in innumerable internet “memes” and artistic expressions including the hit song “George Bush Doesn’t Care About Black People” by The Legendary K.O. Not long after the song became widely disseminated, I watched a class in which the history teacher working with a music teacher explored with students the song’s meaning for questions about race, class, justice and the relationship between artistic and political expression.

Following the 2011 reauthorization of the Patriot Act, a teacher in another school employed a critical reading of the Phil Ochs song “Power and Glory” compared alongside the national anthem as an entrée into a discussion of patriotism.

These are only three examples of history teachers using music in the classroom. There are thousands of others. using music to stimulate engagement in history teaching is not a new idea. I only want to draw attention to the potential of music to help teachers:

- Pursue strong notions of critical thought and democratic habits of mind

- Push back against an education reform movement that faces away from those goals

Music can allow teachers to raise fundamental questions not only about history, progress, politics, and the common good, but also about the aims of education itself. What did we teach in school today?

Music, history and the power of hope

My teacher education students sometimes get annoyed with me for pointing out all the problems with schooling in North America. They learn that in the past two decades, education goals, broadly speaking, have become increasingly technocratic, individualistic, and narrowly focused on job training. As teachers about to enter the profession, they do not want to assume that too many of the lessons that inspire hope have been put on the back burner. They recognize that there are many wonderful teachers doing wonderful work, but they worry that the kinds of lessons in participation and democratic action that give meaning to teaching and learning tend to be opportunistic rather than systematic — based on an individual teacher’s courage rather than on programmatic muscle — and episodic rather than consistent and enduring.

Educators face many obstacles to improving schooling, and history teachers are no exception. Today, we trust teachers less and less and standardized tests more and more. Reform policies at the highest levels are made without any evidence that they will work. And students are treated alternately as blank slates waiting to be trained, as clients waiting to be served, or as consumers waiting to buy. With those kinds of anemic educational goals, the history teacher’s work is bound to be both undervalued and constrained. In some schools, the entire school day is reduced to almost nothing but test preparation in only two subject areas: math and literacy. At the same time (and I think not unrelatedly), reported rates of depression and alienation among young people have skyrocketed. Accordingly, we prescribe medications to a shockingly high percentage of students to make them attentive and “normal.” In a phenomenon reminiscent of Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegone where “all children are above average,” some schools have now deemed the majority of students “not normal.”

Meanwhile, elaborate reward and punishment systems are instituted to keep students engaged. It sometimes seems that in the quest to improve students’ focus and interest, the only thing we are not trying is to actually make the curriculum interesting and worth focusing on. In the face of these conditions, it would seem easy to lose hope. I would like to suggest two reasons why we don’t have to. First, overall reform trends never dictate what is possible in individual classrooms. In the end, it is the teacher who is with students day in and day out. And we all know that teachers, especially those powered by hope and possibility, can and do make tremendous differences in children’s lives.

suggest two reasons why we don’t have to. First, overall reform trends never dictate what is possible in individual classrooms. In the end, it is the teacher who is with students day in and day out. And we all know that teachers, especially those powered by hope and possibility, can and do make tremendous differences in children’s lives.

Second, as the playwright and statesman Vaclav Havel observed, hope is not the same as choosing struggles that are headed only for success: “Hope… is not the conviction that something will turn out well,” he wrote, “but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out” (2004, 82). Hope requires, as the historian Howard Zinn eloquently wrote, the ability “to hold out, even in times of pessimism, the possibility of surprise” (2010, 634). From orchestral scores to jazz to folk, gospel, protest music, and hip-hop traditions, music has often served similar aims. The singer-songwriter-activist Holly Near expressed this artfully in her anthem to the many social change movements that have existed for as long as there have been things to improve. Change does not always happen at broadband speeds, but knowing one is part of a timeless march towards good goals makes much of what we do worthwhile. In her song The Great Peace March, Near (1990, track 8) sings: “Believe it or not / as daring as it may seem / it is not an empty dream / to walk in a powerful path / neither the first nor the last…”

The use of music in history teaching can help refocus the discipline on human experience and the struggle for a better society.

Neoliberal education reforms have hindered efforts to fully articulate an education agenda that recognizes critical thinking, social justice and democracy as important curricular goals. The use of music in history teaching can help refocus the discipline on human experience and the struggle for a better society. If I could hope for one certainty in the lessons each student takes from his or her history education, it would be this: the knowledge that — whether in the face of successes or setbacks — we are, as Near so eloquently sings, walking in a powerful and worthwhile path and that there is a place in that powerful path waiting just for you.

Joel Westheimer is university Research Chair in Democracy and Education at the University of Ottawa and education columnist for CBC Radio’s Ottawa Morning and Ontario Today shows. His newest critically acclaimed book is What Kind of Citizen: Educating Our Children for the Common Good (Teachers College Press, 2015). He is currently directing (with John Rogers, UCLA) The Inequality Project, investigating what schools in North America are teaching about economic inequality. He tweets his bi-weekly CBC Radio broadcasts at @joelwestheimer

ENDNOTES

¹ My thinking along these lines developed while I was working on a chapter for the Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education (2015), edited by Cathy Benedict, Patrick Schmidt Gary Spruce, and Paul Woodford. Parts of this essay are adapted from that chapter and from my book, What Kind of Citizen? Educating Our Children for the Common Good (Teachers College Press, 2015).

² Maxine Greene (2006) credits John Dewey with reminding us that “facts are mean and repellent things until we use imagination to open intellectual possibilities.” From Jagged Landscapes to Possibility. Journal of Educational Controversy, 1(1), Winter 2006, p. 1.

³ Although I refer here to the innumerable examples of music being employed in the service of hope and possibility for social justice, music, of course, has also served less noble aims including totalitarianism and oppression.

REFERENCES

Alinsky, S. (1965). The war on poverty — political pornography. Journal of Social Issues. 11(1), 41-47.

Greene, M. (2000). Releasing the imagination: Essays one education, the arts, and social change. New york: Teachers College Press.

Greene, M. (2001). Variations on a blue guitar: The Lincoln Center Institute Lectures on Aesthetic Education. New york: Teachers College Press.

Greene, M. (2006). Jagged landscapes to possibility. Journal of Educational Controversy. 1(1), 1.

Havel, V. (2004). An orientation of the heart. In P. Loeb (Ed.), The impossible will take a little while: A citizen’s guide to hope in a time of fear (pp. 83 — 9). New york: Basic Books.

Horsely, S. (2015). Facing the music: Pursuing social justice through music education in a neoliberal world. In C. Benedict et al. The Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education. Oxford, uK: Oxford university Press.

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. (2001). Standards for Professional Development Schools. Retrieved from http://www.ncate.org/ documents/pdsStandards.pdf.

Near, H. (1990). Great peace march. On Singer in the Storm [CD]. Hawthorne, CA: Chameleon Music Group.

Stern, S. (2006). “Social justice” and other high school indoctrinations. Front Page Magazine. 14 April 2006. Retrieved from www.psaf.org/archive/2006/April2006/ SolSternSocialJusticeandotherIndoct041306.htm.

Westheimer, J. (2015). What kind of citizen? Educating our children for the common good. New york: Teachers College Press.

Wasley, P. (2006, June 16). Accreditor of Education Schools Drops Controversial ‘Social Justice’ Standard for Teacher Candidates. Chronicle of Higher Education. The Faculty, A13.

Zinn, H. (1980/2010). A People’s History of the United States: 1492 — Present. New york: Harper & Row