Education workers and the public good

Note: As this article is published, CUPE education workers and the Ontario government have reached a tentative deal. According to Laura Walton, head of the CUPE’s Ontario School Board Council of Unions (OSBCU) “no new funding to guarantee that services will be provided in schools for students.”

Here’s a question for the next Education Quality and Accountability (EQAO) math assessment. It could actually be a useful one:

The Minister of Education, Stephen Lecce, says that students across Ontario have been out of class on account of strikes 2 246 days (“to be precise”) since 1989. There are 194 instructional days for in-school learning each year. Why doesn’t this make any sense?”

This is from a tweet Mr. Lecce sent out on November 16 when he called on CUPE education workers to fold their tents, take “yes for an answer and cancel the strike” adding in another tweet that day: “These children have been through enough and it is wrong that every few weeks, ever so casually, strike notices are being imposed on children, on their working parents and on our economy…”

The minister’s claim about school time lost to strikes makes no sense, because if you do the math (2246 / 190 school days per year) it means students have been out of school – due to strikes – for 11 ½ school years since 1989. If you check the figures for all education-related actions back to 1987 when there was a big teachers’ strike, and pretend that all strikes kept all students in the province out of school – though they didn’t – you get a grand total of 90 – that’s 90 days in 35 years. Mr. Lecce is just making stuff up to throw against the wall and see how much might stick. You can check out the strike history below.1

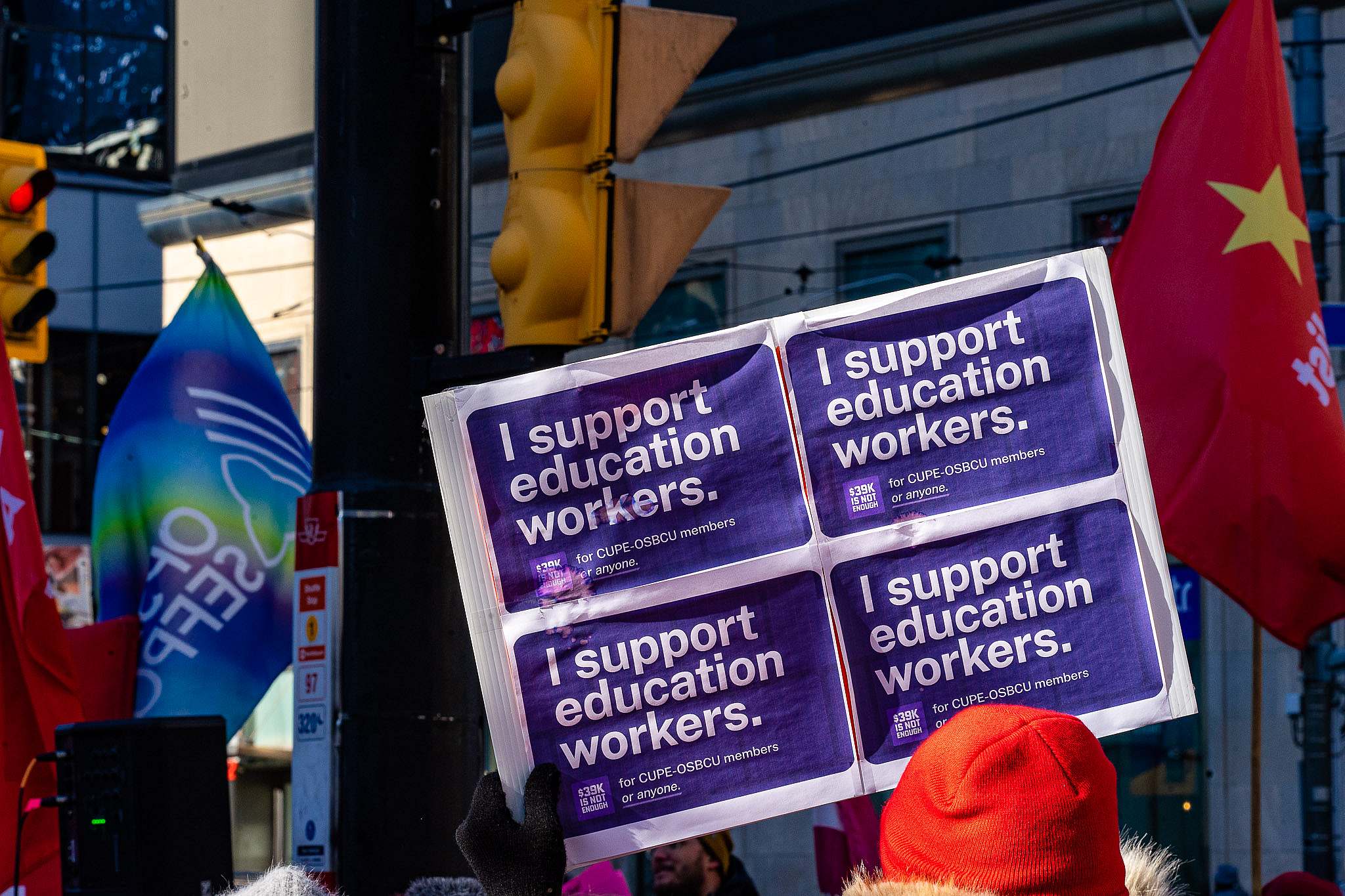

The crocodile tears were about CUPE’s Ontario School Board Council of Unions (OSBCU) calling for a new strike after talks broke down over demands for higher staffing levels for education assistants, maintenance workers, caretakers, librarians and early childhood educators. OSBCU president Laura Walton told a news conference that the $1 hour increase in each of 4 years of the proposed agreement is “a win for workers.” But, after 167 days of negotiating, the struggle was about more than a pay increase.

The crocodile tears were about CUPE’s Ontario School Board Council of Unions (OSBCU) calling for a new strike after talks broke down over demands for higher staffing levels for education assistants, maintenance workers, caretakers, librarians and early childhood educators. OSBCU president Laura Walton told a news conference that the $1 hour increase in each of 4 years of the proposed agreement is “a win for workers.” But, after 167 days of negotiating, the struggle was about more than a pay increase.

What OBSCU wanted

Missing from the news about the latest strike action that was set to begin on Monday are basic demands OSBCU made public days ago. They called on the Ford government to ensure:

-

- that there are enough education assistants (EAs) to meet the specialized needs of kids in school who might get sent home of there is no EA available on a given day

- an early childhood educator (ECE) in every kindergarten class so that 4 and 5-year-olds get the support they need after two years out of school due to the pandemic.

- that libraries have the workers to keep them open for students

- that there are the caretakers and tradespeople available needed to maintain schools properly and tackle the over $16-billion-dollar repair bill

OSBCU called for a strike to help repair education in Ontario – what other workers will need to do in their respective sectors like health, social services and, of course, education. These low-paid CUPE education workers have seen the $800 per student funding cut for 2022-23, the plan to cut 6 000 teachers from schools by 2024, the elimination of a $235 million Special Education fund in 2019 and decades of unmet promises to repair schools, some of which are in such bad shape it might be cheaper to pull them down. They decided that their fight with the Ford government was about more than a wage increase. Sure, they were looking for work for future colleagues, but why shouldn’t they? Schools need help and the Tories would rather buy votes by giving hundreds of millions of dollars to parents to get a little support for their kids rather than put it into schools, where the money will go farther and be more effective. That kind of foresight is not in the cards for a government set on privatizing public goods.

OSBCU called for a strike to help repair education in Ontario – what other workers will need to do in their respective sectors like health, social services and, of course, education. These low-paid CUPE education workers have seen the $800 per student funding cut for 2022-23, the plan to cut 6 000 teachers from schools by 2024, the elimination of a $235 million Special Education fund in 2019 and decades of unmet promises to repair schools, some of which are in such bad shape it might be cheaper to pull them down. They decided that their fight with the Ford government was about more than a wage increase. Sure, they were looking for work for future colleagues, but why shouldn’t they? Schools need help and the Tories would rather buy votes by giving hundreds of millions of dollars to parents to get a little support for their kids rather than put it into schools, where the money will go farther and be more effective. That kind of foresight is not in the cards for a government set on privatizing public goods.

Negotiating for the public good

Contrary to what some like Martin Regg Cohn of The Star might wonder about OBSCU’s apparent inability to say “yes” to a deal, education workers have taken on the responsibility of public sector workers to poke the Tory bear. The Tories are in a great position to be poked, set on their back foot after making a mess of Bill 28, Putting the Public Sector In Its Place Act, rescinding it just as the ink dried. And they keep bullying ahead with new legislation to cut deeper into local democracy in Toronto, just as we begin to learn about the wonderful benefits for Tory supporters who just happen to own land in the newly opened-up Greenbelt.

Education workers went up against the Ford cronyocracy. But the difference is they were pitching to restore public goods – not take them away. In this way, they join with the United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) who, in 2019, went out on strike for better wages and benefits but also for improvements for their communities – more school librarians, nurses and counsellors, more support for immigrant families, more green space around schools. They’re pushing in the same direction as the Baltimore Movement of Rank and File Educators (BMORE) who pushed their union local to become a political force for making improvements in Baltimore neighbourhoods. Educators have become more militant across the U.S. in places like Chicago and West Virginia as well as Milwaukee, where the Milwaukee Teachers Association (MTEA) in 2011, fought against then Wisconsin governor Scott Walker’s efforts to strip public sector unions’ bargaining rights as he cut education funding across the state.

CUPE education workers understood that the importance of their role in public life goes beyond demanding much-deserved increases in pay. It also stands on their ability to organize the fierce opposition that caused Doug Ford to blink, put his agenda into disarray and even make people wonder why underpaid workers’ demands include retrieving schools from the dark hole into which they are descending. This probably makes no sense in a world where self-interest is god.

But more power to these education workers and others who will follow them as they negotiate contracts in the coming years. In coming days we’ll learn more about what drew their job action to a close. The public good is at stake.

¹CUPE education workers have never shut schools down due to strikes – rescinding Bill 28 voided any reference to strike action and the two days in question were widely supported protests of jaw-dropping overreach by a government that uses the “notwithstanding clause” like a rag to wipe a bit of dust off the table. OPSEU, the other union that represents education workers like IT specialists, Child and Youth Workers, lunchroom monitors and Early Childhood Educators haven’t shut schools due to a strike.

That leaves teachers who under OSSTF, AEFO, ETFO and OECTA, have indeed gone on strike to improve wages, working conditions and protest anti-democratic legislation trying to diminish collective bargaining rights over the years.

A brief history:

-

- 2019 – 20 Ford government: 2 full day walkouts affecting high schools, rotating 1-day strikes over a week affecting public elementary schools; 1 full day strike affecting Catholic schools; 2 province-wide walkouts by ETFO affecting all public elementary schools; another 1 day walkout affecting students in Ontario’s French schools and a final big one in which all unions took part. Total days out of class due to strike action: 8

- 2013- Wynne government: Protests began in September 2012 over the Liberals’ Bill 115 (later repealed) which limited unions’ ability to strike, removed banking of sick days and imposed 1.5 percent pay cut on teachers in the form of 3 unpaid PA days. Provincial walkouts were planned but quashed by the bill which cost the province $212.5 million in payouts to educators after it was found to be in violation of collective bargaining rights. Total days out of class due to strike action: 0

- 2012- McGinty government Protests to Bill 115 (see above) with rotating strikes across the province during December. Total days out of class due to strike action: 1

- 2003 – Toronto Catholic DSB locked out teachers who had been without a contract for months. Total days out of class due to strike action: 0 Total days out of class due to a board lockout: 12

- 2002- Simcoe-Muskoka secondary teachers legislated back to work after 3-week strike over wages and working conditions. Total days out of class due to strike action: 15

- 2002 -Simcoe-Muskoka Catholic teachers: Voluntary arbitration after 2-week strike: Total days out of class due to strike action: 10

- 1998 – York Region elementary teachers: After a work to rule the board locked teachers out for 5 days. Teachers responded with 1-day rotating strike. Total days out of class due to strike action: 1 Total days out of class due to a board lockout: 5

- 1998 – GTA teachers from 8 school boards. Back to work legislation ended strikes and lockouts by school boards. Total days out of class due to strike action and lockouts: 15

- 1997 – Days of Action across Ontario to protest the Mike Harris government and his “Common Sense Revolution which cut taxes – along with social assistance, merged school boards and cities and challenged right to collective bargaining. Educators struck illegally – to protest Bill 160 and the gutting of Ontario education. Total days out of class due to strike action: 14

- 1987: Metro Toronto ( prior to the Toronto DSB) elementary teachers over prep time Total days out of class due to strike action: 26

Total – 90 days

Sources:

Canadian Union of Public Employees

University of Toronto: Ontario – A Selection of Notable Strikes https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/c.php?g=250906&p=1680318

Toronto Star: Teacher strikes: Ontario strikes and lockouts since 1987 https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2015/05/04/teacher-strikes-ontario-strikes-and-lockouts-since-1987.html