From the picket line – a week in the life of a strike

Stephen Lecce and the future of education

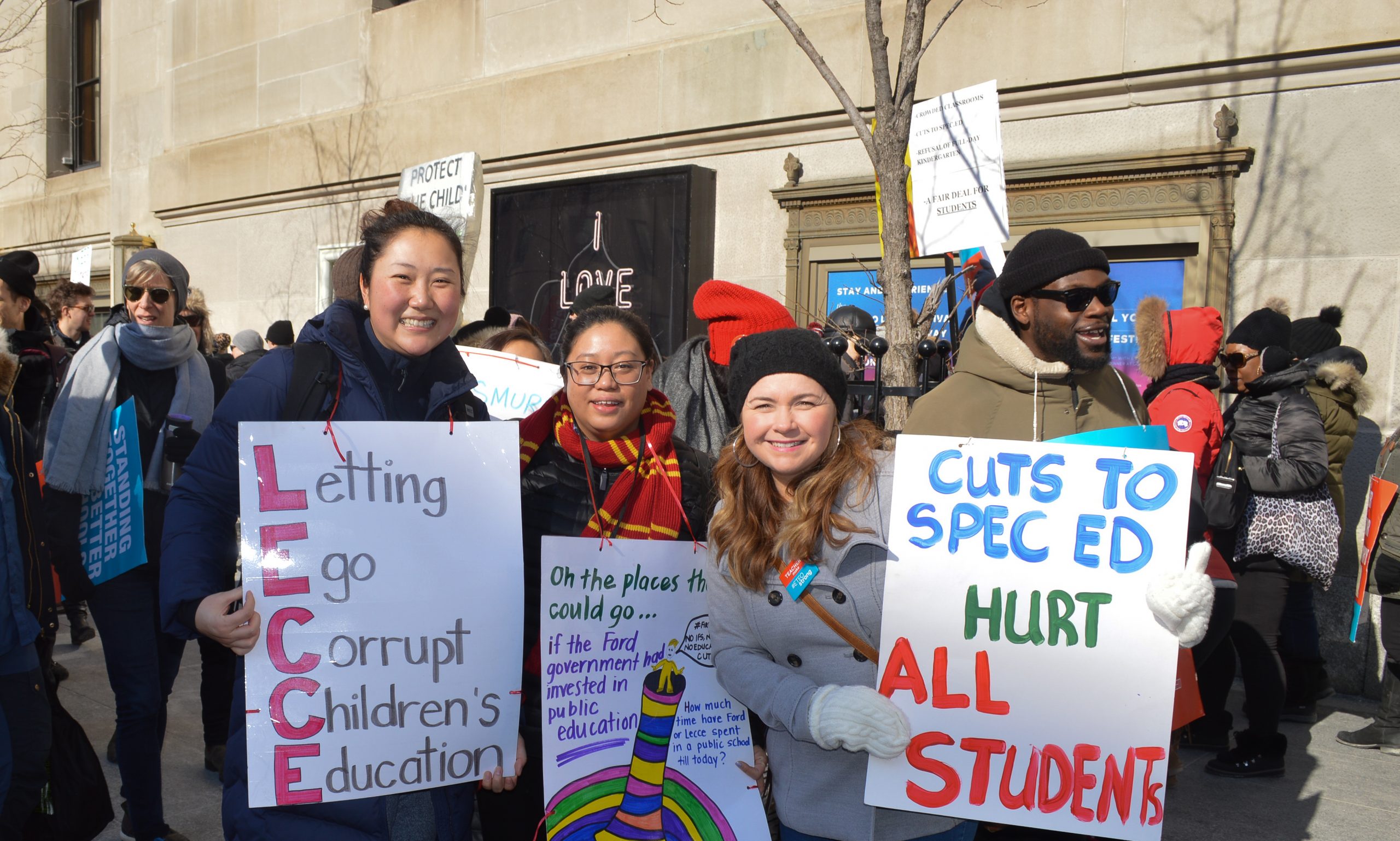

On a beautiful sunny Wednesday this week, 700 to 1 000 Early Childhood Educators and Occasional Teachers filled the sidewalk in front of the Royal York Hotel in downtown Toronto. Inside and up a couple of floors, Minister of Education Stephen Lecce was telling those gathered at the venerable Canadian Club about the future of education in Ontario.

The difference couldn’t be more stark. Outside, the signs and chants were about preserving full day kindergarten, special education funding, eliminating mandatory e-learning and restoring class sizes. Inside Mr. Lecce was explaining that the policies of his ministry will make education better.

I am certain they won’t but, nonetheless, represent the Tory future of education.

Mr. Lecce, claimed to the Canadian Club audience that the Tories have spent more on education that any other government in Ontario history – not a tough claim to defend in that costs typically rise with inflation. This increase is actually more sleight of hand than adding anything new. Writing about the Ford government’s fall economic update Ricardo Tranjan of Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) said, of the $186 million increase, $122 million was earmarked to help municipalities with childcare programs after these costs were downloaded to municipalities. The remaining $64 million went to support “elementary and secondary programs” – most likely the math strategy, funding for mental health supports, and the expansion of the Specialist High Skills Major program. These items used to be covered by the Education Programs Grant until the name was changed to Priority and Partnership Funding and $157 million was lopped off it.

Mr. Lecce, claimed to the Canadian Club audience that the Tories have spent more on education that any other government in Ontario history – not a tough claim to defend in that costs typically rise with inflation. This increase is actually more sleight of hand than adding anything new. Writing about the Ford government’s fall economic update Ricardo Tranjan of Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) said, of the $186 million increase, $122 million was earmarked to help municipalities with childcare programs after these costs were downloaded to municipalities. The remaining $64 million went to support “elementary and secondary programs” – most likely the math strategy, funding for mental health supports, and the expansion of the Specialist High Skills Major program. These items used to be covered by the Education Programs Grant until the name was changed to Priority and Partnership Funding and $157 million was lopped off it.

Then there’s the remaining fact of the 2019-20 budget introduced last spring. Before the Doug Ford came into office, the education budget was set to increase by 3.4 percent to $31.5 billion for 2019; the amount considered necessary to keep up with inflation and demand. Mr. Ford’s education budget came to $29.8 billion – substantially different from that claim about more spending than any other Ontario government in history.

Mr. Lecce’s conception of the future of Ontario education appears to contain a heavy dose of union busting. He says that the “system has been in part designed by and for the unions of this province” He’s going push back on regulation 274 which he claims makes hiring entirely based on union seniority. As far as the rest of the vision, it was limited to increasing mental health and special education supports and “strengthening marketability” of Ontario’s kids through programs like the unresearched and unsupported mandatory e-learning.

As for the current strikes of educators across the province, the minister stayed on script – despite the government’s reasonable offers, unions are intransigent and won’t come to the table to settle a wage dispute. He pushed for a private mediator, when there’s already one appointed by the Ministry of Labour. As for his claim that he did better with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) offering to out hundreds of education assistants into schools – that plan has yet to materialize.

are intransigent and won’t come to the table to settle a wage dispute. He pushed for a private mediator, when there’s already one appointed by the Ministry of Labour. As for his claim that he did better with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) offering to out hundreds of education assistants into schools – that plan has yet to materialize.

Outside, it may as well have been a different planet.

Regulation 274 – Hiring Practices

Up until recently Education Minister Stephen Lecce was saying that the dispute between the Ford government and Ontario’s educators was just about wages. That doesn’t seem to have been too convincing, so recently he has set upon Regulation 274 as a major problem for equity in hiring across the province. You have to hand it to him, he’s good at turning an argument generally used against his government – to his purpose.

Regulation 274 came into effect in 2012 – 13 and set out the rules for school boards to hire teachers for long term occasional and permanent teaching jobs on their staffs. One of its key aims was to reduce the amount of nepotism in hiring teachers and make a more clear and accountable method. Here are the basics: It says that schools boards must rank occasional teachers according to seniority and experience and maintain a list of them. Occasional teachers who have been on this list for at least 10 months and have worked for the board for at least 20 days over a school year, may apply to be put on the long-term occasional list. This list is comprised of occasional teachers who fill in for permanent teachers who are away from school for extended periods.

I f a school board needs to hire someone for a permanent teaching job, one of its representatives interviews 5 teachers from the long-term occasional list who have worked a long-term assignment for at least 4 months, have the required qualifications for the position (my emphasis) and have the highest seniority on the occasional teachers list.

f a school board needs to hire someone for a permanent teaching job, one of its representatives interviews 5 teachers from the long-term occasional list who have worked a long-term assignment for at least 4 months, have the required qualifications for the position (my emphasis) and have the highest seniority on the occasional teachers list.

It doesn’t say anywhere in the regulation, as Mr. Lecce claimed in a Toronto Star interview last December, that “it is really the challenge that impedes the ability of boards to make decisions based on merit or equity is Regulation 274, which creates some impediments to hiring talented educators based on their qualifications.” Any school board may hire occasional teachers with diverse backgrounds, experiences and qualifications – who then may apply for jobs as long-term occasional teachers and, after demonstrating their chops as teachers in long term assignments, may apply for a permanent job with a school board.

A consulting firm, Directions Evidence and Policy Research Group produced a report in November 2014 on Regulation 274 for the Ministry of Education.

On the plus side, Directions reported that with Regulation 274, came an “orderly path to permanent teaching with occasional teaching as the normal or primary point of entry to the profession.” More teachers were being interviewed for positions as more of them became known to principals. School boards reported that more senior occasional teachers were getting a crack at a job. Better teachers were at the front of their classes now that principals had to do thorough performance appraisals. It reported “no instances” where the regulation resulted in a teacher without the necessary qualifications hired into a position – contrary to Mr. Lecce’s claim that principals have “to choose a phys -ed teacher to teach math.”

There were problems too: lack of mobility for experienced teachers between school boards, more grievances because of conflicts in interpreting why teachers didn’t make it to the long term occasional list and discouragement leading young people out of the teaching profession. Boards complained about the challenge of evaluating teachers and that there was no way to remove someone from the long-term occasional list. Unions complained that school boards weren’t providing relevant information about job postings, that older teachers weren’t being considered for assignments that could lead to full-time jobs.

There is much more in the report. But the upshot is that Mr. Lecce is looking for a bargaining trip hazard – something the unions should not give up, that will keep them on the picket lines so he can keep complaining that they’re stubborn – all the while building his case for back-to-work legislation.

Special Education Funding

Last week, Minister of Education Stephen Lecce told John Oakley of Global News radio that, on the special education file “we care deeply about these kids … in special education funding we are spending more in special ed than any other government in the history of Ontario.” (minute 8:52). Let’s take a closer look at this statement. That “more in special ed” claim actually amounts to $3.1 billion for 2019-20. In 2018-19, the Ministry of Education (under the Liberals), budgeted $3.01 billion. Taking the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) recommendation of 3.4 percent annual increase to account for inflation and demand into account, that amount should have increased to $3.1 billion anyway. See above for more information about how additional education funds were spent.

In practical terms, does even $3.1 billion meet the needs of these kids and their schools. One of the main answers to the question: “Why are you  out on the picket line today?” was about state of special education in our schools. Teachers reported over and over again, there are plenty of Individual Education Plans (IEPs) for kids with special needs, but no resources for implementing them. It’s become a joke, that the IEP is the support, not people who can actually help a student. During picketing a week ago, one teacher told me that she had a class of 20 grade 1 and 2 kids. Three of these, she said, were “out of control” and she spends most of her time keeping them pacified as the others wait for her attention. Teachers routinely talk about violence in the classroom: kids throwing furniture, a computer tossed out of a second floor window, teachers and assistants being hit by kids.

out on the picket line today?” was about state of special education in our schools. Teachers reported over and over again, there are plenty of Individual Education Plans (IEPs) for kids with special needs, but no resources for implementing them. It’s become a joke, that the IEP is the support, not people who can actually help a student. During picketing a week ago, one teacher told me that she had a class of 20 grade 1 and 2 kids. Three of these, she said, were “out of control” and she spends most of her time keeping them pacified as the others wait for her attention. Teachers routinely talk about violence in the classroom: kids throwing furniture, a computer tossed out of a second floor window, teachers and assistants being hit by kids.

Integration has, over the last decade or so, become the ideology of special education: these kids should be in the classroom with their peers. In most cases this makes sense, but integration has to come with a lot of support and it was clear from talking to teachers, it just isn’t there. Needy kids are struggling in regular classrooms, where there isn’t the time, expertise and aren’t the adults to help them. One teacher from Sprucecourt PS, in downtown Toronto clued in when she was urged to go to workshops on special education. The TDSB had just cut teachers because of the shortfall in last year’s budget and she could see the writing on the wall – less of those teachers = more high needs-kids in my regular grade classroom.

Meanwhile, don’t forget the other shoe that will drop if the Ministry decides to cut school board budgets again. That’s where it can still do a lot of damage. In the last TDSB budget for example, 21.5 support positions got the axe. These are the people who might be able to tell teachers how to deal with high needs kids in their classrooms- psychologists, speech and language pathologists and social workers.

Add all of this to increased average class sizes and you have a disaster.

Hospital Schools

As School has mentioned in the past, it is critical to listen to parents to keep their support. As strikes continue, the pressure on parents to find alternate care for their kids only increases. This is especially true for families whose children attend school in hospital locations across the province – kids with serious physical and emotional needs. These are schools that operate under hospital boards according the Ministry of Education and include the Niagara Children’s Centre Authority, the John McGivney Children’s Centre Authority in Windsor, the Campbell Children’s School Authority in Oshawa, the Bloorview School Authority in Toronto, the KidsAbility School Authority in Waterloo and CHEO School Authority in Ottawa.

Earlier this week, QP Briefing reported that these schools would be closed during strike days. ETFO President Sam Hammond told a press conference last week: “Our strikes are a matter of solidarity among ETFO membership. All members are participating in these strikes regardless of location. For those locations which are hospital locations, it means that educational services will not be provided for a strike day but children will still get the care they need.”

This is certainly the right thing to do. These are vulnerable boys and girls who need ongoing care and supervision. But there are different responses to the strikes. Dayna Giorgio, spokesperson for KidsAbility in Waterloo, told me that the centre would be closed during days when teachers and support staff are on strike. Bloorview is open to secondary students but is closing its educational programming for elementary kids while it provides recreational programs for them. Its kindergarten and grade 1 programs for community students are closed during strikes, though they can still attend clinical appointments. At CHEO in Ottawa, it’s a bit more complicated, because of the number of programs the centre provides. According to spokesperson Paddy Moore, inpatients won’t receive teaching services but, of course, are supervised. For classes in local schools, students can still attend them but will receive only therapeutic, not educational, services. CHEO school itself deals with students whose needs aren’t at the same level as those in its other programs and it will be closed during strikes.

But there are different responses to the strikes. Dayna Giorgio, spokesperson for KidsAbility in Waterloo, told me that the centre would be closed during days when teachers and support staff are on strike. Bloorview is open to secondary students but is closing its educational programming for elementary kids while it provides recreational programs for them. Its kindergarten and grade 1 programs for community students are closed during strikes, though they can still attend clinical appointments. At CHEO in Ottawa, it’s a bit more complicated, because of the number of programs the centre provides. According to spokesperson Paddy Moore, inpatients won’t receive teaching services but, of course, are supervised. For classes in local schools, students can still attend them but will receive only therapeutic, not educational, services. CHEO school itself deals with students whose needs aren’t at the same level as those in its other programs and it will be closed during strikes.

While he’s a lot smoother than his predecessor, Stephen Lecce is making claims that he can’t support in light of his government’s plans to cut funds for services across the province. He is building a case for back-to-work legislation, rather than making a meaningful offer like rescinding his class size increase and mandatory e-learning; he could also be clear about maintaining full-day kindergarten and special education support. We may see where he’s headed after all Ontario teachers from kindergarten to grade 12 hit the picket lines next Friday February 21.

Teacher quote of the week:

“I was in grade 3 during the last strike and now I’m a teacher in my 30’s and looking at having my own kids one day. This is for them.”